Fashion diplomacy and the perils of overzealous style statements

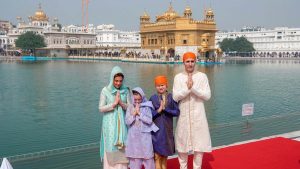

Justin Trudeau poses for a family photo at the Sikh Golden Temple in Amritsar. AFP

Canada’s prime minister Justin Trudeau has been mocked at home and abroad for his cosplay take on diplomacy during a recent tour of India, which illustrates the perils of overzealous political style statements that seek to outrun political reality.

For a whole week, the entire Trudeau family was photographed in a range of colourful, luxurious, sequined or embroidered outfits more normally seen in Bollywood films, lavish television soap operas and at big fat Indian weddings. Along with the sherwanis and saris, the Trudeaus joined their palms in the traditional Hindu “namaste” greeting. It is too Indian for Indians, complained one commentator. Certainly the effect was overly staged, when fashion diplomacy must be barely evident if it is to be effective at all.

One of the more fascinating instances of clothes being used to build bridges between countries comes from the 18th century and involves a man. Benjamin Franklin, America’s first ambassador to France, presented his credentials to King Louis XVI in a brown suit and plain fur hat, which endeared him to a people weary of the excesses of the court of Marie Antoinette. Franklin clearly divined the mood of the country where he was to represent America.

Not so Mr Trudeau, apparently. The Canadian prime minister’s Liberal Party nurtures its substantial and vocal Canadian Sikh vote base. This is seen by India to promote a secessionist agenda for a splinter state called Khalistan. Mr Trudeau arrived in India with a full wardrobe of Indian outfits but without having distanced himself from the separatists. Accordingly, fashion diplomacy became a fashion disaster.

More traditionally though, clothing has been a successful message board. Fashion diplomacy has generally been the preserve of women. For decades, the British Queen has used her wardrobe to transmit a flattering message to the country she’s visiting. Sometimes, it was a colour-coded form of sartorial communication, such as a dress and coat in yellow, Australia’s national colour. Or a turban-style hat in Saudi Arabia to indicate respect for local custom. A crystal Irish harp brooch made especially for a state visit to Ireland. A dress adorned with China’s national flower for a visit to Beijing. Or with Californian poppies to meet the late US president Ronald Reagan, a former governor of California. The idea of using clothes as a form of diplomatic outreach is popular with female leaders and first ladies. When the Queen of Spain visited Britain last year, she offered a canny diplomatic tribute to her host country’s fashion industry with a claret trench coat by Burberry.

Until recently, so-called “frock diplomacy” was generally left to women and it was most eye-catching when it was subtle. But before his fashion blowout in India, Mr Trudeau had created a new political style for male leaders. Christened sock diplomacy, it works through themed socks for public occasions. The prime ministerial ankles have been emblazoned with Eid Mubarak at the end of Ramadan, sported the colours of the Nato flag for a North Atlantic Treaty Organisation meeting, been covered in Canada’s maple leaf symbol for a provincial heads of government conference, and on International Star Wars Day, they referenced Stars Wars. “Rarely have a man’s ankles said so much,” wrote a major American newspaper, and it was truly, a subtle but striking male accessory to the usual diplomatic toolkit of dresses, symbolic brooches and earrings employed by women.

Considering Mr Trudeau’s adept anklewear diplomacy it’s hard to understand how he got it so wrong in India. “Can we look forward to Mr Modi dressing up as a Mountie when he visits Canada?” asked an exasperated Indian commentator in reference to India’s prime minister Narendra Modi. Axios, an American news website that’s increasingly popular for its trademark “smart brevity”, ran a photograph of the Trudeau family in Indian garb under the headline: “Which public figure had the worst week in the world?” Shree Paradkar, a columnist for the Toronto Star, Canada’s best-selling broadsheet newspaper, described the culture overkill as patronising, “over the top”, “groan-inducing” and like “a cliched Bollywood drama”. In an acerbic comment piece for a leading Indian newspaper, Candice Malcolm of the Toronto Sun suggested Mr Trudeau’s successes “can be traced more to his talents as a performance artist than to an understanding of statecraft, economics or diplomacy. When posing in a costume, he is at his best.”

But in India, he clearly wasn’t, despite appearing in an array of costumes. The reasons are obvious and not all of them are to do with clothes.

Unwittingly, Canada’s prime minister may have become a textbook example of the do’s and don’ts of fashion diplomacy. These are simple: less is more, and style must always be subservient to political substance.

India-Canada economic ties are not particularly robust and the Khalistan issue has the effect of a shroud.

In the circumstances, a tasteful pair of prime ministerial socks bearing a map of undivided India might have done the trick. And set a new South Asian fashion for well-dressed ankles.