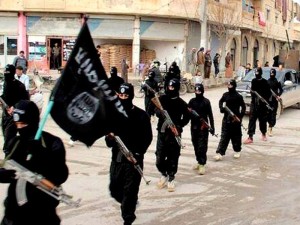

The Sufi Maghreb is struggling with the attraction of IS

If there can be any measure of IS’ extremist imprint on the Maghreb, it is found in a Sufi celebration in the beautiful village of Sidi Bou Said.

If there can be any measure of IS’ extremist imprint on the Maghreb, it is found in a Sufi celebration in the beautiful village of Sidi Bou Said.

| The village, on the fringes of the Tunisian capital, was a great favourite with visitors before this year’s extremist attacks felled the all-important tourist industry. Every so often, Sidi Bou Said bares its Sufi soul with processions that sing the anthem of love for god and life. At a recent celebration, I was approached by an older woman, and asked if I understood exactly what I was watching. |

“Yes,” I answered, but she continued, “This is not Daesh, I hope you know that.”

I was taken aback by her reference to the Arabic acronym for IS. And her need to reassure that Tunisians are not in hock to the extremist group’s agenda.

In late June, right after the murder of 38 western tourists on a beach in idyllic Sousse, south of the Tunisian capital, a group calling itself Ajnad Al Khilafa de Kairouan warned foreigners against visiting Tunisia. Its choice of name was significant. Kairouan, established in the late 7th century, is Tunisia’s holiest city.

More Tunisians are known to be fighting with ISIS than any other foreign nationality. The International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) says that as of January, five countries in the Greater Maghreb — Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia — provided an estimated 5,350 fighters to extremist organisations in Syria. The ICSR puts the number of Tunisians fighting with ISIS at 3,000.

It’s not just the unemployed and the dispossessed that leave Tunisia to fight for extremist causes. Nearly two years ago, the nephew of Tunisia’s former ambassador to India was killed fighting for IS in Syria. So are Tunisians unnaturally predisposed to extremist Islam?

There are two theories. First, the lack of economic opportunity in a well-educated, predominantly youthful country, four years after the Jasmine Revolution that toppled the dictatorship of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. Secondly, southern Tunisia has been relegated to the sidelines of the more fashionable story — a mindset to match the Mediterranean influences on food and light on religion.

From 1956, when it became independent of France, secularism was projected as the new country’s main article of faith. Its first president, Habib Bourguiba, and his successor, Ben Ali, ruled 55 years between them, a period in which the state suppressed Muslim education and frowned upon the public practice of Islam.

The 2011 revolution changed all that and opened up society in a way that allowed preachers to brainwash young people with fiery talk of jihad. At the same time, the release of 2,000 men who had been imprisoned for being Islamists led to the formation of the Tunisian terrorist outfit Ansar Al Sharia.

This can help contextualise the post-2011 surge in Islam, but it does not explain why Tunisians, even before the Arab Spring, travelled to Afghanistan, the Balkans, Iraq and Lebanon to fight for the extremist cause.

If the conundrum is the consequence of a basic chasm within Tunisia — the religiously orthodox, marginalised south vs the westernised, prosperous north — there is little indication of a more inclusive social architecture being built. Or, more troublingly, that it is even on the drawing board.

(Rashmee Roshan Lall is a senior journalist on Twitter:@rashmeerl. The views expressed are personal)