Did Suki Kim write on North Korea because of remembered memory?

Pyongyang, December 19, 2011 and Suki Kim is in North Korea, where it is “Juche Year 100.” Kim Jong Il has just died.

Pyongyang, December 19, 2011 and Suki Kim is in North Korea, where it is “Juche Year 100.” Kim Jong Il has just died.

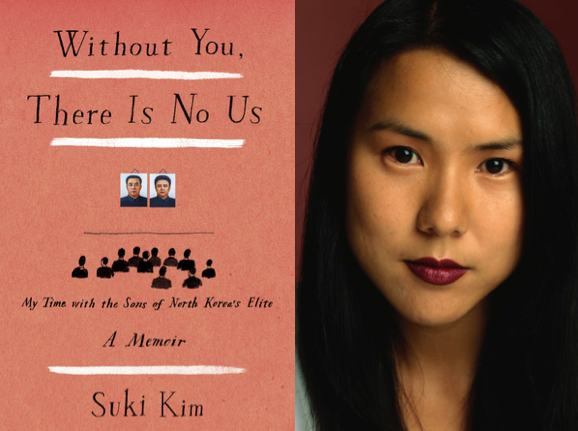

“The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) follows a different calendar system,” she explains in her memoir ‘Without You, There Is No Us’.

It “counts time from the birth of their original Great Leader, Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994”.

Ms Suki, who grew up in South Korea and first visited the North in 2002, wrote about teaching English to the sons of North Korea’s ruling class during the last six months of Kim Jong Il’s reign. She did it secretly and very secretively, she has been telling curious journalists, writing every day that she was in North Korea, transferring the material to a flash drive and then deleting it all from her computer.

This is how she managed to provide a view from inside, of inside. Such as, the fact that every day, three times a day, the students march in two straight lines, singing praises to Kim Jong-il and North Korea: Without you, there is no motherland. Without you, there is no us.

Gradually Ms Suki learns the tune and, almost without noticing, begins to hum it too.

She finds her young charges enthusiastic and curious about all she tells them – and this includes surfing the internet, travelling freely, political freedom – but when they are totally devastated at Mr Kim’s death, she thinks there might be too great a chasm between her world and theirs.

And yet, as she writes in the following excerpt, she felt more at home in Pyongyang than in America where she had lived from the age of 13.

“Strangely, in 2002, when I visited Pyongyang for the first time, I felt more at home than I had since I left Seoul as a child. There was a sense of recognition. The past was all right there before me: generations of Koreans separated by division; decades of longing, loss, hurt, regret, guilt. I identified with it in a way that I could never shake off. I thought that if only I could understand the place, then I could find a way to help put the fragments back together. Like most Koreans, whether from the North or South, I dreamed, perhaps irrationally, of reunification. I returned repeatedly until 2011.”

Does this make a point about the cultural continuum, a place of a remembered memory transmitted through DNA? As Jhumpa Lahiri wrote in ‘The Lowland’, “What was stored in memory was distinct from what was deliberately remembered, Augustine said”.