The Rosetta Stone was the time machine by which ancient Egypt reached us

Walk like an Egyptian, just don’t do what they did about cultural preservation. Or what they didn’t do.

Walk like an Egyptian, just don’t do what they did about cultural preservation. Or what they didn’t do.

They didn’t do much to transmit their civilization through the ages, as Grayson Clary points out in his fascinating Aeon piece.

Some of Egypt’s civilisation has been recovered, but some was lost irretrievably, he writes. “For all its carven glyphs, Egypt cannot claim to have passed down its dreams, memories and hopes for the future… Imagine the pharaohs’ frustration at all the bits of language lost, the prayers and tributes especially. This was a civilisation that had its eyes fixed on eternity.”

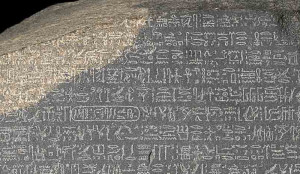

The transmission loss is mainly on account of the hieroglyphic script, which suffered through centuries of illegibility. As Mr Clary points out, the last dated hieroglyphic inscription is 394 AD, at Philae, a small Nile island that hosted a temple to the goddess Isis. It would be incomprehensible till the 19th century.

For years, scholars puzzled over the allegorical meanings of a lion’s forelegs or the depiction of a windpipe, but the language isn’t fully phonographic or ideographic.

It was not till the French scholar Jean-François Champollion considered a cast of the Rosetta Stone, which had been picked up from Egypt by Napoleon’s army, that the Pharaohs would once again be heard by the world. The stone, as Mr Clary reminds us, “records the same message three times, in three scripts, one of which was well understood in Napoleon’s day. The trilingual stone saved what could be saved from an entire civilisation’s cultural memory. It was the time machine by which ancient Egypt travelled into the future.”

So how do we get our own Rosetta Stone? How do we safeguard ourselves from the same sort of incomprehension in the future? How do we enable those who come after us to retrieve information across vast cultural divides and immense stretches of time?