A sad loss. The US army version of T. E. Lawrence for Afghanistan’s war

Today, July 29th, it’s exactly a month since the US army ended a seven-year experiment that had its heart in the right place: with the people the Afghan war was meant to help.

Today, July 29th, it’s exactly a month since the US army ended a seven-year experiment that had its heart in the right place: with the people the Afghan war was meant to help.

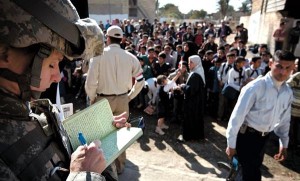

At the end of June, the military confirmed that it was calling time on the rather sinisterly named Human Terrain System programme. For those who’ve never heard of it (and there’s no reason you should have) HTS deployed social scientists in Afghanistan alongside the US military. This was to provide cultural input to military decisions. Wags might say it was a sort of 21st century American version of deploying multiple Lawrences in the Afghan equivalent of Arabia.

Critics of the HTS complain it was a waste of US taxpayers’ money – $100 million a year – and woolly military tactics anyway since the anthropologists sent into the combat zone neither knew the local language, nor were they trained to defend themselves.

Critics of the HTS complain it was a waste of US taxpayers’ money – $100 million a year – and woolly military tactics anyway since the anthropologists sent into the combat zone neither knew the local language, nor were they trained to defend themselves.

That does sound really rather extraordinary though some might argue that a somewhat similar fate befalls US Agency for International Development (USAID) workers in Afghanistan. When we were there, not all that long ago, USAID contractors in Kandahar, Badghis PRT and other faraway places used to be referred to as “tethered goats”. Another way to describe them might be “sitting ducks”.

Anyway, back to the HTS. As Tobin Harshaw put it earlier this month on Bloomberg View, the programme had an intriguing premise: “The sociocultural insights of academics embedded into special operations and other units in Afghanistan could give commanders on the ground an edge in fighting the Taliban and encouraging cooperation from local citizens. Most importantly, a better understanding of local culture and mores could lead to less pointless bloodshed.”

Mr Harshaw writes that a government study subsequently found that HTS was pretty “effective in training soldiers on the ‘dos and don’ts’ of Afghan culture”. Apparently, the social scientists also helped put together “detailed profiles of villages in the combat zone.” And the overwhelming majority of military commanders regarded their contribution as very useful when making decisions. The examples are revealing and I, who have long been involved in looking at USAID “success stories”, believe at least some of this.

For instance, the link a social scientist identified between widowhood and insurgency in the Shabak Valley in eastern Afghanistan. The area had many widows and their sons, who ha to look after them, fell prey to Taliban recruitment (and pay). This led to finding a way to get the widows involved in the textile trade, which allowed their sons to travel further afield and find jobs.

All of this sounds very good. So why has it ended?

It seems that like so many US military innovations, it was set up with huge flaws and spun in an unreal fashion.

Finally though, it just wasn’t well-run and was taken down by widespread corruption and mismanagement.

But it was a good idea. Perhaps one day it will be revived with a new name.