In Kairouan, Tunisia, north Africa’s only manuscript restoration workshop

The Museum of Islamic Art in Raqqada near Kairouan in central Tunisia is a truly remarkable place.

The Museum of Islamic Art in Raqqada near Kairouan in central Tunisia is a truly remarkable place.

It was gifted to the nation by Habib Bourguiba, the newly independent country’s first president, who ruled for 30 years.

Here’s the rather grand conference room.

I’ll expound more fully on the Museum’s treasures in a subsequent blog. Suffice it to say, there are many.

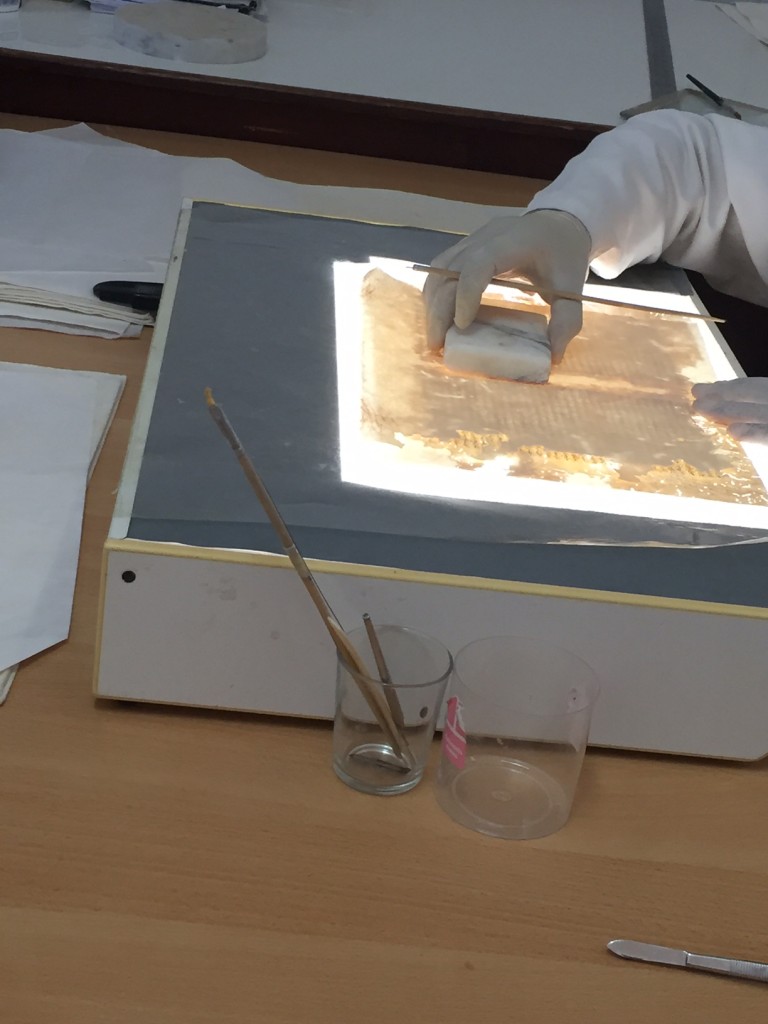

Today, though I’m going to provide an inside view of a part of the Museum that almost no one sees. We were lucky enough to be given a tour of the manuscript restoration department tucked away in one corner of the Museum.

It’s supposed to the only one of its kind in north Africa and Tunisia owes a great deal to the Germans, who helped set it up. Here’s the head of the manuscripts department.

Note the plaque in memory of Gunnar Brannahl, head of conservation in Gottingen and the first director of the cultural-assistance project funded by the German foreign ministry and carried out by the Library of the State and University of Lower Saxony in Gottingen.

Note the plaque in memory of Gunnar Brannahl, head of conservation in Gottingen and the first director of the cultural-assistance project funded by the German foreign ministry and carried out by the Library of the State and University of Lower Saxony in Gottingen.

After Dr Brannahl’s 1986 death, Roswitha Ketzer took charge. As this report by Ms Ketzer records, the project’s objectives were “the conservation of Arabic manuscripts; the training of three Tunisians as archive conservators and a Tunisian photographer as a micro-filmmaker; and the establishment of a conservation workshop and a microfilm studio.”

The project came about when Professor Brahim Chabbouh, then Director General of the National Library in Tunis, visited a similar German conservation project in Yemen. The agreement to work on the conservation of Arabic manuscripts in Kairouan was signed on July 15, 1985.

The project came about when Professor Brahim Chabbouh, then Director General of the National Library in Tunis, visited a similar German conservation project in Yemen. The agreement to work on the conservation of Arabic manuscripts in Kairouan was signed on July 15, 1985.

I think the Germans were probably persuaded of the importance of Kairouan’s treasure trove because, as the report records, it “is the only large Tunisian city that does not date back to antiquity, but was founded by the Arabs.”

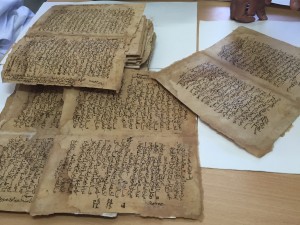

The German effort was well done – for that time – and the Manuscripts Department still relies on the microfiche machine the Germans installed in 1989. It currently has roughly 60,000 manuscripts dating as far back as the 9th century, which is a huge increase on the numbers recorded when the German project began. At the time, there were “70 to 100 separate Koran manuscripts on parchment; 1,500 separate non-Koran manuscripts on parchment; 2,500 separate Koran and non-Koran manuscripts on paper”.

When the project started, the manuscripts were in poor condition. The parchment ones, had “water damage and holes eaten away by insects, rats or other vermin.” Roswitha Ketzer’s report says that “some pages have been so deformed that they look like balls. The writing on the parchments has in many cases cracked off or melted, and the silver ornamentation has oxidised.”

The paper manuscripts were hardly better, infested with mould and “attacked by insects … on account of the glue of animal origin that was used”.

The papyri ones, according to the report were “in a fragile condition and almost transparent.”

When the Germans started work alongside the Tunisians, 80 per cent of the manuscripts dated from the 9th to the 11th century.

Only 20,000 of the manuscripts have been restored so far and considering the time it takes – one year per book on average – millennia would pass before we were able to find out what these writers from the past had to say. An awful lot of them are Korans, in which case, there’s a lot less mystery.

But still a lot of magic.