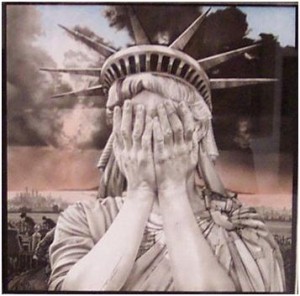

Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric is affecting the United States

Sadiq Khan, London’s newly elected mayor, used the first 24 hours after his win to denounce the anti-Muslim campaign waged against him. Khan said his rival Zac Goldsmith, with the overt support of British Prime Minister David Cameron, had deployed tactics “straight out of the Donald Trump playbook”.

Sadiq Khan, London’s newly elected mayor, used the first 24 hours after his win to denounce the anti-Muslim campaign waged against him. Khan said his rival Zac Goldsmith, with the overt support of British Prime Minister David Cameron, had deployed tactics “straight out of the Donald Trump playbook”.

It was an obvious reference to Trump’s anti-Muslim remarks on the campaign trail. The Republican Party’s presumptive presidential nominee started saying he wanted to ban Muslims from entering America in December, right after the mass shooting by a married Muslim couple in San Bernardino, California. He focused on the threat from Muslim foreigners even though the San Bernardino shooters were legally present in the United States — the man was US-born-and-bred and of Pakistani ethnicity; his Pakistani wife had a green card as a consequence of the marriage.

Six months later, Trump is still talking up the threat posed to the United States by Muslim foreigners, though he graciously says he will make an exception for Khan and permit him to enter the United States.

But it is clear there is a playbook. First, because Trump no longer needs inflammatory rhetoric to, in his favourite word, “win” his party’s nomination for president. As of May 4th, he was the last man standing in the Republican race. Trump could conceivably offer a new vision for America, one that would be based on building up rather than striking down. That he does not want to suggests there is “a Trump playbook”.

It is already having a devastating effect but not in any way that makes Americans feel safer.

Consider this. On May 5th, a 40-year-old, olive-skinned man with curly dark hair, was the reason a domestic American Airlines flight was delayed for a couple of hours and returned to the gate. The man, an Italian Ivy League economist named Guido Menzio, had committed the following offence: scribbling differential equations into a notebook for a lecture he was to give in Ontario.

Menzio, who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, had been reported by another passenger worried about the security implication of the foreign lettering on which he was so focused. The economist was able to convince security personnel that he was writing mathematical equations, not plans in Arabic to blow up the plane.

The incident comes just a month after Khairuldeen Makhzoomi, an Iraqi refugee student at the University of California, Berkeley, was taken from a domestic flight for having been overheard speaking Arabic. A panicky fellow passenger reported Makhzoomi because she confused the word inshallah with shaheed or martyr.

Both incidents might seem no more than a ludicrous coincidence and almost laughable if they were not so serious.

Menzio, whose equations were so terrifying for an ordinary American traveller, offers a troubling diagnosis. He has confessed to being troubled by the ignorance of his fellow passenger and by a security protocol “that relies on the input of people who may be completely clueless”.

And he blamed the rising xenophobia stoked by the ongoing US presidential campaign. “What might prevent an epidemic of paranoia?” he told the Washington Post. “It is hard not to recognise in this incident, the ethos of Trump’s voting base.”

Clearly, the Trump playbook is creating dramatic subscripts in all sorts of ways for people who happen to look different in America. Swarthy. Middle Eastern. It might be called “flying while looking suspicious”.

There is, as Trump earlier put it in relation to Muslims and the United States, “something going on”. There is something going on but it is not what he says it is.

America is afflicted with fear. And it is the result of the Trump playbook.

There can be no other reason for the sudden onset of paranoia nearly 15 years after 9/11, when America is, arguably, as safe as it is possible to be. In 15 years, there has not been another terrorist attack that was planned abroad and executed on American soil.

After some teething troubles — and allegations of ineptitude and brutality — the vast US Department of Homeland Security has pretty much settled into its role. It was created a year after the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which was folded into it. The TSA, signed into law two months after 9/11, has done a fairly decent job of overseeing security for highways, railways, buses, mass transit systems, pipelines, ports and more than 450 US airports across the country. US President Barack Obama has been known to frequently remind his aides that terrorism takes fewer lives in America than guns and accidents in bathtubs and on the road.

But the Trump playbook is spinning a dangerously different storyline and it is having the intended effect.