It happened after the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris in January 2015. Then again in November after a series of explosions rocked various venues in the French capital. And in March when three coordinated bomb blasts tore through Brussels. The world — or at least international news outlets and social media networks — responded with extensive coverage, visible shock, cries of solidarity and the tender promise of heartfelt prayers for the victims and their families.

It happened after the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris in January 2015. Then again in November after a series of explosions rocked various venues in the French capital. And in March when three coordinated bomb blasts tore through Brussels. The world — or at least international news outlets and social media networks — responded with extensive coverage, visible shock, cries of solidarity and the tender promise of heartfelt prayers for the victims and their families.

However, when terrorist attacks ripped through Turkey, Bangladesh, Iraq and Saudi Arabia during the last week of Ramadan, the world seemed to mourn differently. Some said it reacted almost with indifference.

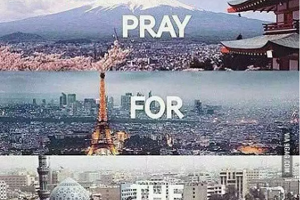

Were too many tears shed for Paris and Brussels and too few for Istanbul, Dhaka, Baghdad, Jeddah, Medina and Qatif? Is there really a hierarchy of grief? A different calculus of loss for the West and the rest?

That is certainly the way it is perceived by some. Anne Barnard, the New York Times’ Beirut bureau chief, recently reported on the outrage over insufficient global outrage about the deaths in Iraq, Turkey, Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia. Approximately 300 people died at the hands of terrorists and yet the carnage did not trigger a collective planet-wide mourning. Some people complained.

They meant that the modern tech-enabled rituals of grief were conspicuous by their absence. Hashtags such as #PrayForIraq did not trend after the bombs went off July 3rd in Karrada and Shaab in Baghdad. Facebook profiles did not become stiff with the sympathetic fluttering of Turkish, Bangladeshi, Iraqi and Saudi flags during that week of horror in the Muslim world. The Eiffel Tower, Brandenburg Gate and other iconic European structures were not lit in the colours of those countries. Are they second-class triggers of global grief then?

Yes, for all the pleasing fiction that everyone everywhere can aspire to care equally about everyone else anywhere.

There are some valid reasons for news editors and social media junkies to pay a tad more attention to a terrorist strike in Europe rather than the Middle East and South Asia.

First, France and Belgium are not in the same state of conflict-ridden, long-term disarray as Iraq. Consequently, bad news from Iraq seems a great deal less surprising than from the heart of mainland Europe.

Second, Turkey does not prompt the world to identify with it in the way of many other countries. So, too, Saudi Arabia.

For Turkey, this is largely because of its increasingly erratic president with his faux fatwas on a range of controversial social and cultural matters such as women’s patriotic duty to procreate.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s administration is also accused of inhibiting free expression and a baleful pattern of hostility and human rights abuses towards the Kurds.

As for Saudi culture, it may seem unfathomable to many beyond its borders. Remember UCLA psychiatry Professor Marco Iacoboni’s explanation of the global outpouring of sympathy for terror-hit Paris and the tearful blooming of the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag: “We tend to empathise more with people who we feel are more ‘like us’.”

Third, Bangladesh’s impenetrable troubles. They fail to provoke much sympathy largely because the wider world is unable to understand them. More than 40 people — secular bloggers, gay activists, academics and members of religious minorities — have been killed in attacks blamed on Islamist militants since February 2013.

As Ramadan came to a close this year, the Islamic State (ISIS) claimed responsibility for a high-profile attack on a hip café in Dhaka but the government blamed misguided local youths and opposition parties.

This has had an unfortunate effect. With each murderous attack on a secular blogger or thinker and each phlegmatic response from the establishment, the inaccurate impression grows that the country’s gentle culture of moderation is hardening into a radically violent form of Islam and that most Bangladeshis support the change.

There is another, more general reason that some countries provoke less global sympathy than others. Their own political leaders do not seem to care enough, which gives outsiders the excuse to take their pain less seriously.

We have been here before. In January 2015 to be precise. In the same week as the Charlie Hebdo attacks, hundreds of Nigerians were reportedly killed by Boko Haram militants. The world focused on Paris, not Baga.

Was this solely because of the double standard of measuring grief? Or was it at least partly the result of the manifest silence and unconcern of African media and political class?

Even Nigeria’s then president, Goodluck Jonathan, took care to express his condolences for the victims in France but stayed silent on the Boko Haram attacks. It may have been politically expedient to ignore a terrorist group that had grown in prominence on his watch but the Nigerian leader’s disregard of his own people’s pain appeared to devalue it.

All too often, the same sort of callous calculation marks the reaction to violence in parts of the Muslim world. A sectarian filter is applied to conflict and suffering, especially when the lives lost are local. This has made for an angry realism on the Arab street and other populous parts of the developing world: life is cheap here.

How then to reckon up the calculus of loss?