If we can’t unite around a ‘global history’, what hope for coalescing around culture?

Reading Princeton professor Jeremy Adelman’s thoughtful, thought-provoking piece on global history in Aeon magazine, I was reminded of French philosopher Regis Debray’s fulminations on the dialogues between cultures.

Reading Princeton professor Jeremy Adelman’s thoughtful, thought-provoking piece on global history in Aeon magazine, I was reminded of French philosopher Regis Debray’s fulminations on the dialogues between cultures.

That was round about the point when Professor Adelman talked of global history as a narrative “fit for the now-defunct Clinton Global Initiative”.

It was meant to be, the professor wrote, “a shiny, high-profile endeavour emphasising borderless, do-good storytelling about our cosmopolitan commonness, global history to give globalisation a human face.”

So to Debray and the notion of cultural harmony. He wasn’t buying it. To expect cultural dialogue is to promote a “contemporary myth”, he said. Science and technology, said Debray, can provide the foundation for a shared world but not culture, which is “a natural place of confrontation, since it is where identity is forged, and that in turn presumes a minimum of dissent.”

If that sounds exceedingly dismal, Debray notably went on to cite Claude Levi-Strauss and observed that civilisation contains within itself the coexistence of extremely diverse cultures and lives precisely from this coexistence.

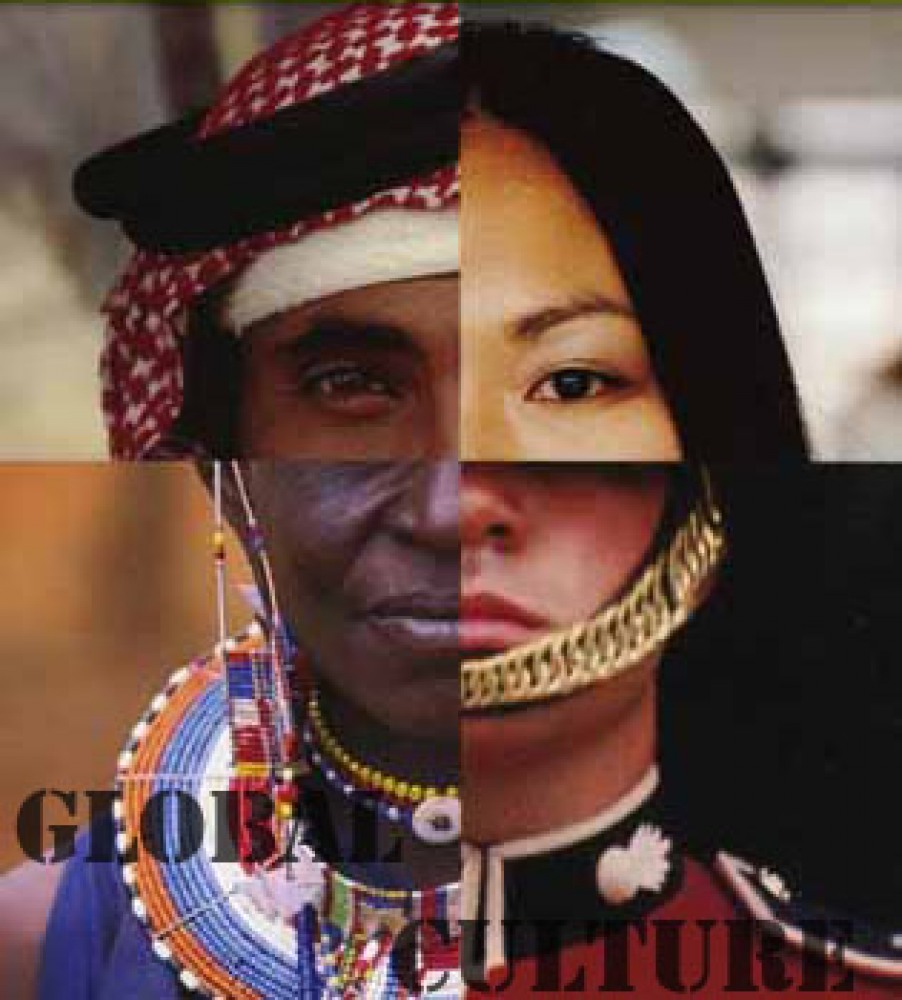

What this really means is that it is as futile to speak of a global culture (or even a universalised one, despite our smart phones and social media) as it is to speak of a global history.

Cultures are as distinct as nations’ (and peoples’) histories.

But just as Debray and others since have said, cultures are disparate and distinguished by shifting and flexible boundaries.

So too perhaps global history?

There isn’t one narrative, and certainly not one perspective. Subaltern views in different parts of the world have their own (stubborn) take. And the victors often get to tell certain key parts of the story.

But if it fuses different bits of the world map, it’s global history, n’est ce pas?