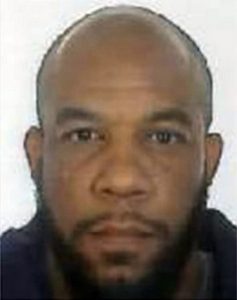

Soon after the March 22 violence perpetrated outside the British parliament by a man named Khalid Masood, the old argument over terrorism and publicity was revived.

A prominent British journalist went on the BBC to criticise its wall-to-wall coverage of Masood’s crime. That’s what it was, former Sunday Times editor Simon Jenkins insisted — a serious and tragic crime, but a crime nonetheless. It was no different, he said, from past attacks by the IRA and the PLO, and it was unwise to describe it with a “tremendous clutter of politics and Islam and religion”. The hysteria, said Jenkins, did the terrorists’ job for them because “terrorism is just a method of getting publicity”.

It was a restatement of British prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s July 1985 exhortation to “find ways to starve the terrorist and the hijacker of the oxygen of publicity on which they depend”. Thatcher spoke at a time when the issue was just as controversial as today. Live Aid — Bob Geldof’s concert to raise money for Ethiopia’s famine victims — had just taken place. It had drawn hundreds of thousands of people and through satellite link-ups, was watched by nearly two billion around the globe.

Thatcher noted the marvellousness of using “the magic of technology to restate in the language of pop the age-old brotherhood of man”. But the same satellites, she pointed out, also brought home to everyone “the savage threat of terrorism”. She meant television’s ability to terrify people by bringing violence into their homes. It was the age of hijackings rather than lone attacks on the streets of European cities. Just weeks before Thatcher’s speech, an American plane flying from Athens to Rome was hijacked by Hizbollah and forced to land in Beirut. Its passengers and the United States government were subjected to a 17-day ordeal during which a Navy SEAL was killed. But the US and British governments, said Thatcher, were united on a key point: “The law will be applied to them (terrorists) as to all other criminals.”

This was the deliberate strategy employed by many governments at the time. It was seen to prevent hijackers from presenting themselves as glamorous outlaws.

Thatcher followed up her remarks by ordering a broadcasting ban on supporters of the Provisional IRA, the main paramilitary group fighting to separate Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom. Just like her remarks, Thatcher’s attempt to deny publicity to terrorists became controversial. Katharine Graham, publisher of The Washington Post, wrote in high dudgeon that she was against “restrictions on the free flow of information about terrorist acts” mostly because they are “impossible to ignore”. She said that media silence would allow rumours to flourish and that there was no evidence to show “terrorist attacks would cease if the media stopped covering them”.

Different versions of Graham’s argument have been routinely trotted out over the years since the attacks on New York and Washington on September 11, 2001. The point is well made but it may be time to ask if overdone coverage is doing less to inform than to inflame. Did the non-stop reportage of Masood driving his hired car into pedestrians in central London inspire “Mohamed R”, a 39-year-old French national of North African origin, to launch a similar abortive attempt in Antwerp the next day? Did Masood realise the publicity potential of using a vehicle as a weapon from breathless coverage of similar incidents in Berlin in December and in Nice in July? As Frank Foley, a counterterrorism expert at King’s College London, puts it: “Terrorists rely on a lot of people watching — it can be even better than having a lot of people dead.”

What is the happy medium between media coverage that provides relevant information to the public and one that serves as town crier for terrorists? Is a happy medium even possible in the age of social media, when anyone with a smartphone can put gory footage of an attack online in real time?

Yes, and it could look something like this: when a morose 28-year-old white man from Baltimore recently stabbed a black man to death in New York with a 60cm sword, most American news outlets soberly reported the murderer’s intense hatred for black people. They also recorded his determination to commit a spectacular crime in a city where it would receive massive attention. And that was that. Despite the anecdotal rise of white belligerent nationalism in the United States after Donald Trump’s election, and in parts of Europe, there was no “clutter” of politics, religion and ethno-nationalist hatred to confuse the clear lines of a tragic story. The Baltimore man’s crime was not conflated with every other vaguely similar incident. There was, in short, little hysteria in the coverage, which basically followed the usual lines of crime reporting. That is as should be.

Why is that measured tone lost when covering Masood’s crime in London, the aborted attack by “Mohamed R” a day later and Ziyed Ben Belgacem’s attempt to cause mayhem at Orly airport, to name the three main “terrorist” incidents in Europe this month? Is it because the attackers are all perceived in some way to be advancing the cause of radical Islamists and part of a larger “Muslim agenda” to take over the world and turn it into an Islamic state? If so, the PLO hijackers and IRA fighters also advanced a larger cause even as their violent actions were reported — and adjudicated — as crimes. Somewhere along the way, in the course of the so-called war on terror, we have lost sight of that.