Normally when the words British and jihadi are used in the same sentence, the reference is to what the United Nations calls “foreign terrorist fighters”. That is, westerners who left their countries to fight for ISIL in Syria.

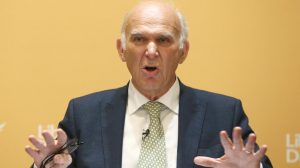

But on Sunday, a prominent UK politician suggested a link between Britain and a different sort of jihad. Commenting on the heightened sensibilities aroused by the British referendum to leave the European Union, Vince Cable, leader of the Liberal Democrat party said, “we haven’t yet heard about ‘Brexit jihadis’ but there is an undercurrent of violence in the language which is troubling.”

It was probably one of the more high-profile attempts by a western politician to examine political extremism of different kinds and discern the common thread that runs through them. A couple of months ago, Tony Blair’s former spin doctor was castigated for tweeting about “Brextremists” and the way they spew “hate”. But Mr Cable’s remarks may be more significant by far. He heads Britain’s third party and is a veteran who has been in active politics since the 1970s. It is noteworthy that he sees jihadism as radicalisation of any sort, rather than that simply caused by a perversion of one faith, Islam.

_______________

More from Rashmee Roshan Lall

Why the dismissal of prime minister Nawaz Sharif failed to generate shock and outrage

Globalism with a local accent is now officially on the political agenda

In Tunisia, a sense of change infuses the air

_______________

Before Brexiteers start to bristle at their project being equated with murderous violence in service of Islam, consider this. In early November, Britain’s second biggest-selling daily newspaper attacked a court ruling on Brexit with front-page pictures of the three judges alongside the headline, “enemies of the people”. Within hours of its publication, Brexit supporters took to social media to call for the judges to be publicly executed and for the main litigant in the case, a foreign-born, brown-skinned woman, to be murdered. The scion of a noble family offered £5,000 on Facebook to “the first person to ‘accidentally’ run over this bloody troublesome first generation immigrant.”

It is a given that social media often provokes, even encourages, extreme commentary and behaviour, but the menacing attempt by sections of the Brexit brigade to throttle dissent by threats and imprecations is a classic manifestation of radicalisation. This is what Mr Cable meant when he spoke of the Brexit jihadis of the future.

The realisation that anyone, from any community, can be radicalised, is important. It has profound policy implications. It confirms a new wave of analysis that views ISIL more as a gang of young people driven by the identity politics of victimisation than as a religious or ideological movement.

This is borne out by a new study for the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Center. It found that young Muslim jihadis see their faith “in terms of justice and injustice rather than in terms of piety and spirituality”. The study, conducted by Professor Hamed El Said of Manchester Metropolitan University and British terrorism expert Richard Barrett, noted that the majority of foreign terrorist fighters interviewed “felt a duty to go to Syria in order to defend what they perceived as their in-group”. Many were religious novices, the researchers said, and lacked even a basic understanding of the Islamic faith. A substantial number of fighters did not know how to pray. But they felt a strong sense of community and a raging sense of injustice.

This chimes with a theory put forward last year by Marc Sageman, a psychiatrist, sociologist and a former CIA case officer, in his book Misunderstanding Terrorism. Communities aren’t enablers or facilitators of radicalisation but they can be the reason for it, Mr Sageman found, after studying 34 campaigns of political violence over 200 years. In other words, men or women may decide to attack a system if they think it is failing their people. In 80 per cent of the campaigns of political violence Mr Sageman examined, people became militant — in word or deed — when they felt their community was threatened in some way.

_______________

More from Rashmee Roshan Lall

Is US facing its Vietnam moment in Afghanistan?

Why austerity threatens future growth of a nation

How extremism has hijacked the UK election

_______________

The alt-right jihad, with Donald Trump espousing some of its main grievances, is a case in point. In the words of an American columnist, “the new Whiny Right (is fighting to protect) the waning power of whiteness, privilege, patriarchy, access, and the cultural and economic surety that accrues to the possessors of such.”

Their perceived victim status is akin to that of misguided youths who happen to be born Muslim and are sufficiently enraged by the state of their community to fight a distant war.

And that victim status is echoed in the ill-tempered, ill-logic of Brexit hardliners. Aggressively touting their sense of ill-usage in relation to the European Union, they argue against all available facts, statistics, expert opinion and economic projections and insist that Britain need only leave the European straitjacket in order to be great again.

Clearly, one does not have to be born into any particular faith to wage a jihad. In an age of mobility and ceaseless change, it is enough to believe it’s Us versus Them and that radical means are justified.