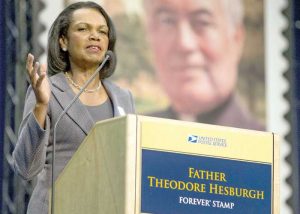

For all those who despair of the patchy and imperfect delivery of democracy after the Arab uprisings that started seven years ago, Condoleezza Rice has news.

Democracy is in fine fettle, she says, or words to that effect. Occasional hiccups matter little in the long term. Just look at the American experience and all will be clear. Rice makes these assertions in her new book “Democracy: Stories from the Long Road to Freedom.”

It’s worth taking note of her views.

Mostly of course because Rice was President George W. Bush’s secretary of state and, before that, his national security adviser. Her attempt at so-called transformational diplomacy, which was supposed to spread democracy around like love, was an important policy platform of the Bush era. And it had blowback.

Rice’s chief claim to fame is her role in the Bush administration’s regrettable attempt to establish democracy in Iraq — by means of war. It doesn’t matter that Rice now insists the invasion was “not for democracy promotion” but was a benign act to topple a brutal dictator.

In March 2004, a year after the invasion, she triumphantly and all too clearly spelt out the Bush-led America’s objectives as follows: “Iraq and Afghanistan are vanguards of this effort to spread democracy and tolerance and freedom throughout the Greater Middle East. Fifty million people have been liberated from two of the most brutal and dangerous tyrannies of our time. With the help of over 60 nations, the Iraqi and Afghan peoples are now struggling to build democracies, under difficult conditions, in the rocky soil of the Middle East.”

It’s another matter that Afghanistan is not in the Middle East but Rice was wrong on other counts, too. The US invasion may have overthrown a regime that no one need mourn but it spectacularly failed to replace it with the organic scaffolding of democracy — local institutions and norms of accountability, limited experiments with local elections to see what works, enabling the slow build-up of different political and civil society groups without paying them for their work.

But on March 19, 2003, the day before the invasion, Rice was declaring “our intention to help the Iraqi people liberate themselves… and to very early on, put in place with Iraqis — from outside the country and inside the country — an Iraq authority that can administer and run the country.” We all know how that turned out.

And yet, Rice defends the Iraq war. She recently indicated there was little to regret and much to celebrate. Without mentioning the hundreds of thousands dead as the result of an illegal attack on a sovereign country, Rice declared: “I would rather be Iraqi than Syrian today. I would rather be Iraqi with a prime minister who might be weak but he’s accountable to the people. With 25 different newspapers and radio stations and Arab satellite available and where my government doesn’t actually use barrel bombs and chemical weapons against me. So when I hear about how poorly the Iraqis are doing, I want to say in regards to what or in comparison to what?”

In this context, Rice makes one crucial contribution to the raging debate around the world about the democratic recession, which has increasingly illiberal democracies such as Turkey, Israel, Russia, Hungary, Poland and India shamelessly franchising a system that allows for elections but fewer freedoms.

She reminds those who’ve lost faith in the flowering of democracy in the Middle East that it takes a long time to build and progress is not linear. There will be backsliding and half-measures.

That bit makes sense. In one-party China after all, village elections were introduced in the 1980s and by 2008 more than 900 million Chinese villagers had exercised their sovereign right to vote for their local representatives.

Sometimes, too, democracy may take the form of unusual start-ups such as the small Syrian town that recently voted for the first time since 1953 in a direct election. Saraqib, in eastern Idlib, chose its local council even though its geography might be considered inimical to ballot boxes. Idlib, it’s worth remembering, was recently described by Brett McGurk, US special presidential envoy to the anti-ISIS coalition, as “the largest al-Qaeda safe haven since 9/11.” Saraqib’s experiment with local democracy has been hailed by Manhal Bareesh of the Syrian opposition but in itself it means little.

Only time will tell if a native strain of democracy will do better than a transplant.