#Zimbabwe: The coup de Grace that wasn’t. Echoes of Egypt?

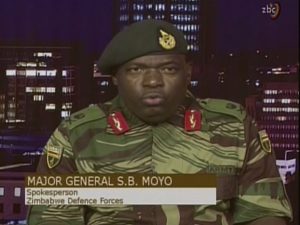

Zimbabwe’s Major-General Sibusiso Moyo insists the action was “not a military takeover”

From Harare, capital of Zimbabwe, the country’s generals have been firm about how to read their actions of Tuesday night.

It’s not a coup, they said. Major-General Sibusiso Moyo said the action was “not a military takeover of government” but a temporary act to prevent conflict. Mr “Mugabe, and his family are safe and sound and their security is guaranteed,” he added. “We are only targeting criminals around him who are committing crimes that are causing social and economic suffering in the country …”

So that’s settled then. It might look like a coup and sound like a coup, but it really isn’t. Not if there’s nifty verbal manoeuvring.

Something similar, you may remember, happened in Egypt four years ago. President Abdel Fatah al-Sissi, then head of the Egyptian army, went on TV to read a statement that ended President Mohamed Morsi’s one-year tenure. The constitution, Mr Sissi said, “is suspended.” But he offered early elections. Egyptians, who had been protesting against the democratically-elected Mr Morsi’s uncompromising rule, cheered. And the international community jumped through several semantic hoops to maintain the fiction that “military intervention” was rather less than a coup.

The then UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon noted the “legitimate concerns of Egyptian protestors” but added that military interference was always “of concern”.

Barack Obama, then US president, avoided the C-word, which might have drawn Congressional action, notably choking off financial aid to a strategically important US ally.

William Hague, then British foreign secretary, decried military “intervention” but noted it was a “popular” move.

Qatar said it would “respect the wishes of the Egyptian people”.

But Tunisia and Turkey called it like it is, mostly because they had was some sympathy for Mr Morsi or for his brand of political Islam . The head of Tunisia’s then-governing, Islamist Ennahda party condemned the “flagrant coup against democratic legitimacy”. And Turkey’s foreign minister said the “military coup” was “unacceptable”.

Back to Zimbabwe, and the military’s removal of Robert Mugabe, 93 years old, and his country’s strongman for 37 years.

Were the military’s actions a necessary intervention that will eventually enable democratic expression and, therefore, be in Zimbabwe’s interest? Does the possibility of future democratic expression make it acceptable for a country’s leader to be removed at will by the military?

Does the difference between Mugabe and Morsi lie in the Egyptian leader’s democratic mandate and the Zimbabwean’s long-held tyranny?

Perhaps.

But surely a coup is a coup? Some might say that accepting military intervention – if a ruler is thought to have lost sufficient political legitimacy – leaves the democratic system forever oscillating between the people’s will and the generals’ free interpretation of it.