John Chau shouldn’t be forgotten. His fatal ‘civilising’ mission has resonance, past and present

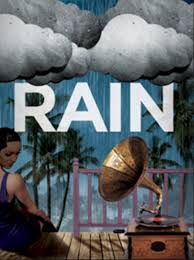

No one’s talking about John Chau any more, but we should. The young man died trying to convert a tiny hunter-gatherer tribe on India’s remote North Sentinel Island. I thought of ‘Rain’, Somerset Maugham’s short story when I first heard about the American missionary.

No one’s talking about John Chau any more, but we should. The young man died trying to convert a tiny hunter-gatherer tribe on India’s remote North Sentinel Island. I thought of ‘Rain’, Somerset Maugham’s short story when I first heard about the American missionary.

Maugham wrote the story in 1921 but nearly a century on, that attitude – puritanical, prejudiced and patronising – is evident in Chau’s unfortunate attempts with the Sentinelese tribe.

Chau’s religious fervour took him where he shouldn’t have gone. Consider what he did. He broke Indian law by making physical contact with the Sentinelese in his attempt to convert them to Christianity. The Sentinelese tribe is thought to number in the dozens, has had almost nothing to do with the outside world, and consequently enjoys legally protected status. I say “enjoys” but it’s more like the Sentinelese suffer no contact with other people and the Indian authorities are conscious of the need to protect them from diseases against which they have not developed immunity.

Chau was very conscious of what he thought to be his divinely ordained duty when he embarked on his illegal mission.

Before he set off to bring the tribe to Christianity, he wrote in his diary as follows: “Lord, is this island Satan’s last stronghold where none have heard or even had the chance to hear your name?”

The diary of Chau’s last days was provided to The Washington Post by the young man’s mother.

Dodging Indian patrols in the waters near North Sentinel Island, Chau must have shrugged of the memory of his initial contact with the Sentinelese. Then, a teenaged Sentinelese shot an arrow at him, which pierced his waterproof Bible. As The Washington Post put it, he still decided to return to the island, “galvanized by the feeling that he was God’s instrument”.

That overweening sense of superiority is reminiscent of ‘Rain’, Maugham’s story about the severely civilising mission of a white missionary, Mr Davidson, and his prim wife, in the islands to the north of Samoa. Mrs Davidson, as Maugham tells it, “spoke of the depravity of the natives in a voice which nothing could hush, but with a vehemently unctuous horror.”

In one conversation with the narrator of the story, Dr Macphail, on board a ship to Apia in the Pacific, Mrs Davidson says: “Can you wonder that when we first went there our hearts sank? You`ll hardly believe me when I tell you it was impossible to find a single good girl in any of the villages. Mr Davidson and I talked it over, and we made up our minds the first thing to do was to put down the dancing. The natives were crazy about dancing.”

As it happens, Maugham’s story ended in the same grim way as that of Chau in 2018. Mr Davidson, Maugham’s missionary, is determined to save the soul of Miss Thompson, a white woman thought to be working the world’s oldest profession –prostitution. He gets the governor of the island of Pago Pago, where the ship has stopped, to run Miss Thompson out. She is to be put on the next boat to San Francisco, when that docks at the island. Miss Thompson is distraught at the prospect – she will be sent to the penitentiary if she returns to San Francisco. In the intervening period, the missionary spends a lot of time in Miss Thompson’s room. He now familiarly calls her Sadie and says he’s wrestling with her “black” soul. “All day I pray with her,” Mr Davidson tells Dr Macphail.

But that wasn’t all he was doing. As Dr Macphail realises after Mr Davidson commits suicide – having cut his throat with a razor – Miss Thompson has seen a side of the missionary he pretended did not exist. After his death, she jeers at the doctor: “You men! You filthy, dirty pigs! You’re all the same, all of you.”

Maugham captured the beating heart of human beings – white, brown, black, Christian, pagan, tribal, 20th century Davidson, 21st century Chau. Ego, passions, self-regard.