A series of disputed elections show the myriad ways in which democracy’s rules are being warped

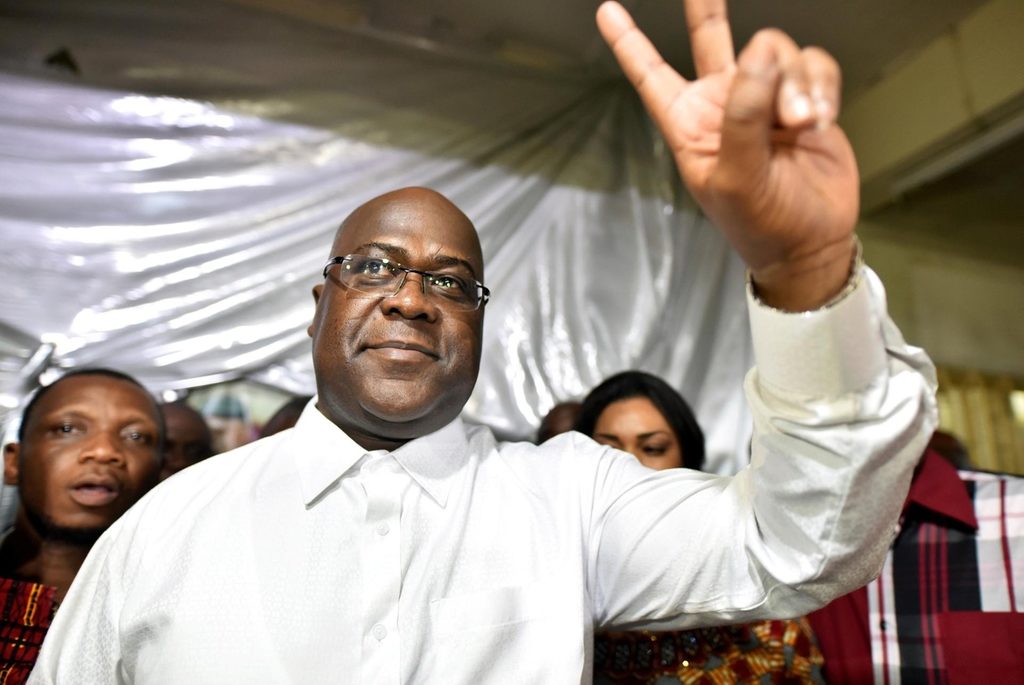

Felix Tshisekedi, leader of the Congolese main opposition party, takes over from outgoing president Joseph Kabila but is accused of striking a deal with him in the disputed election. Olivia Acland / Reuters

From the DRC to Bangladesh and Russia, the manipulation of election outcomes is a worrying worldwide trend

In 2016, a fateful year for democracy in the US and UK, a book with a seemingly contradictory title was published. Against Elections: The Case for Democracy argued it was dangerous to boil democracy down to a foundational requirement of competitive elections. In fact, said Belgian author David Van Reybrouck: “Elections are the fossil fuel of politics. Whereas once they gave democracy a huge boost, much as oil did for our economies, it now turns out they cause colossal problems of their own.”

The recent ballot in the Democratic Republic of Congo could be exhibit A this year in the case against elections. It was supposed to be the first time since independence from Belgium in 1960 that Congolese voters peacefully replaced their head of state. Instead, the ballot — flawed, at times farcical — has been so contentious that the US and France sent troops to the region to keep the peace.

But more troubling by far is the electoral model outgoing president Joseph Kabila is accused of manufacturing — allegedly striking a deal with opposition candidate Felix Tshisekedi to swing the ballot in his favour. It bears all the hallmarks of the trick deployed by Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who in 2008 ensured the election victory of a sidekick to replace him as president until he could constitutionally resume office.

Congolese strongman Mr Kabila is seemingly on the same path, with a handpicked successor on the ballot. That he subsequently accepted the apparent election victory of an opposition leader suggests he has taken the Putin model a stage further by co-opting a less obvious candidate. The end result is that Mr Kabila will remain in power, if not actually in office, only now with the fig leaf of having presided over democratic change.

This is one of the myriad ways democracy’s rules are increasingly being bent — and the wider world isn’t doing much about it. There’s some speculation the declaration of Mr Tshikedi as winner might give regional bodies such as the African Union an excuse to call the DRC’s election mostly free and generally fair. But that is hardly likely to inspire the Congolese and their neighbours with faith in democracy and hope in the legitimacy of elections.

Such manipulation of election outcomes is a worrying manifestation of a worldwide trend. More elections are being held in more countries than ever before but democracy itself is backsliding, with results increasingly disputed. There is a lengthening list of countries that hold regular elections but are steadily making the act of voting less meaningful.

According to the Pew Research Centre, the number of democratic nations is at a post-war high. Nearly six in ten countries have democratic institutions and processes today, with 97 out of 167 countries classed as democracies, 21 as autocracies and the remainder either a mix or unclassified.

But in last year’s Liberal Democracy Index for 178 countries, the V-Dem Project stated: “For the first time since 1979, the number of countries backsliding on democracy is the same as the number of countries advancing”. This is happening in a number of ways. As well as the Russian and Congolese models, there is something called “constitutional retrogression”, the effects of which are apparent in Turkey, Hungary, Poland, India, Bangladesh and even the supposed bastion of democracy, the United States.

The term is defined by University of Chicago Law School professors Aziz Huq and Tom Ginsburg as an “incremental (but ultimately substantial) decay in three basic predicates of democracy — competitive elections, liberal rights to speech and association, and the adjunctive and administrative rule of law necessary for democratic choice to thrive”. It is different from authoritarian reversion, a rapid and near-complete collapse of democratic institutions. Retrogression is slow, sometimes barely perceptible but stunningly effective.

What this means is clear. There are more chances now than say, 15 years ago, of having an election such as the one in Bangladesh, held on December 30, the same day as the DRC. In Bangladesh, the incumbent prime minister’s coalition won an improbable 96 per cent of the vote. There was a time when such an election would have been discredited or at least seriously questioned by the international community, possibly even censured by the Commonwealth. It was marred by weeks of violence, the mass arrest of opposition activists, multiple allegations of voting irregularities and a lack of access for international monitors. But the world has accepted the Bangladesh election, despite indications that the government has used state tools over the years to engineer “retrogression” by weakening the opposition and clamping down on judicial and media dissent.

Elections are no longer synonymous with a healthy democracy. But the irony is that the people’s vote itself is being used to erode democracy.