Unknown knowns?

Three different UK courts have issued three different rulings on prime minister Boris Johnson’s decision to suspend parliament for longer than usual. It’s all very head-spinning even in the age of Brexit. Perhaps only Plato could explain it well.

But first, to recap:

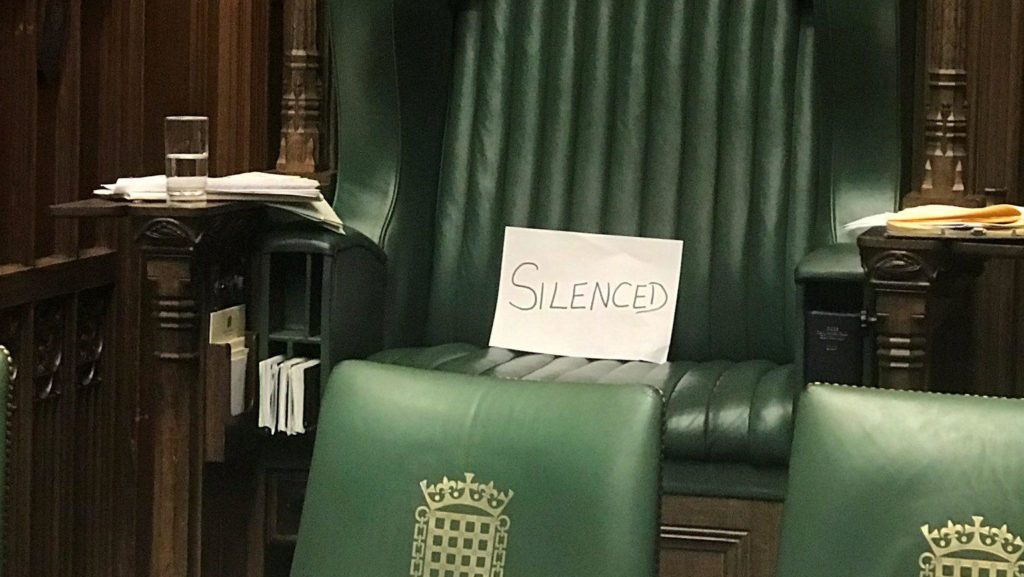

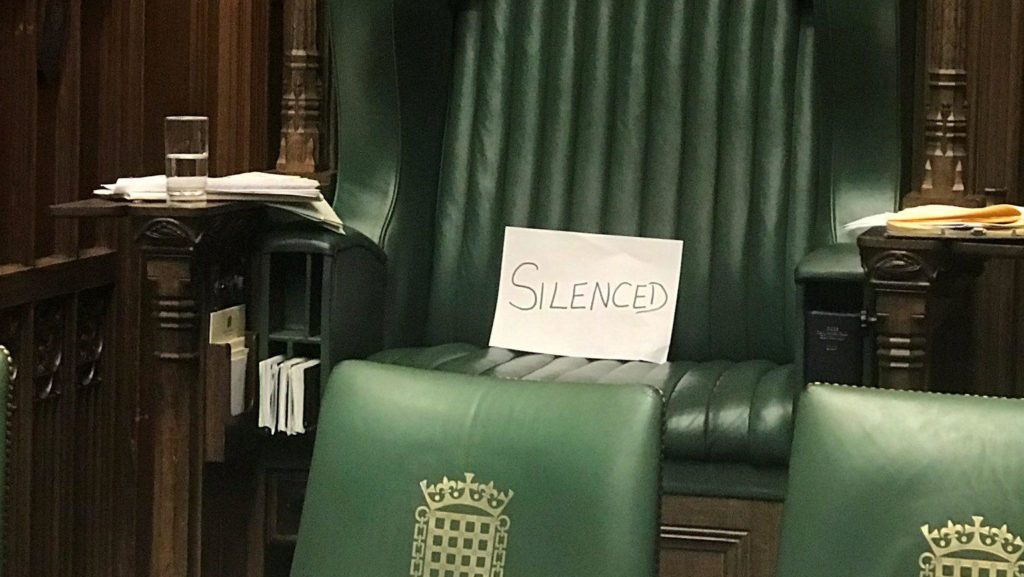

- On Sept. 12, Northern Ireland’s highest court refused to rule on a case that challenged Johnson’s decision, deeming the case “unmistakably political.”

- The day before, Scotland’s highest court had ruled that shutting down parliament was “unlawful,” and that Johnson “was motivated by the improper purpose of stymying” it.

- And on Sept. 6, a London court known as the England and Wales High Court had rejected a case that argued Johnson had engaged in an “an unlawful abuse of power.”

None of these decisions will be the last word on the matter. On Sept. 17, the UK Supreme Court—the highest in the kingdom—will start a three-day hearing to join together all three appeals from the cases in Edinburgh, Belfast, and London.

Where Plato comes in

It is not surprising that the three highest courts in the UK’s separate jurisdictions took different views on a similar question. The issue is broad—it touches on political motivation and the passions aroused by Brexit. It’s a classic illustration of something identified by Plato back in the fourth century BC: There is a distinction between knowledge and belief.

Everyone has opinions about whether or not Johnson was right to suspend parliament for five weeks as the clock ticks down to Oct. 31, the date set for Brexit. And there are several legal opinions about the issue. But no one has any direct knowledge about Johnson’s motivation.

Plato explored the difference between a belief that is only an opinion, and one that qualifies as knowledge, in the dialogue called Theaetetus (p. 201), which features the words of Socrates, his teacher.

In it, Socrates and Theaetetus agree that an opinion must be “true” to be regarded as knowledge. Socrates even notes that there is “a whole profession”—lawyers—who use oratory to get judges to have a particular opinion. In addition, he said, judges, often have true opinions without knowledge.

That’s something the three rulings on Johnson’s suspension of parliament, in three UK jurisdictions, illustrate quite clearly.

That different judges could rule on the same facts in different ways was at the heart of Socrates’ reasoning in Plato’s Theaetetus:

Socrates

…when judges are justly persuaded about matters which one can know only by having seen them and in no other way, in such a case, judging of them from hearsay, having acquired a true opinion of them, they have judged without knowledge, though they are rightly persuaded, if the judgement they have passed is correct, have they not?

Theaetetus

Certainly.

Socrates

But, my friend, if true opinion and knowledge were the same thing in law courts, the best of judges could never have true opinion without knowledge; in fact, however, it appears that the two are different.

Originally published at qz.com

#FBPE #StopBrexit

#FBPE #StopBrexit