Both the US and Europe have a shrinking geography of opportunity

Coincidentally, I read a Brandeis University report on ‘The Geography of Child Opportunity’ in the US the same day I came across a statistic on poverty in western Europe.

According to gross domestic product (GDP)estimates reconstructed by economic historians for nearly 200 subnational regions across western Europe going back a century, regional inequality stopped narrowing from the 1980s and partly went into reverse.

The Brandeis researchers, meanwhile, constructed something they called the Child Opportunity Index (COI), “the first national measure of contemporary child opportunity” in the US and covering all 72,000 US neighbourhoods. The hardest place to grow up, they found, is Bakersfield, California and the best is Madison, Wisconsin. “In the neighborhood of the typical child in Bakersfield, 21% of families live in poverty,” the report said. It seemed a dreadful statistic to come out of the US, the richest country in the world.

But it makes a tragic sort of sense, especially when placed alongside the economic historians’ reconstruction of GDP in 200 subnational European regions. The US has seen a similar trend to Europe in having rich capital regions pull away in economic growth and opportunity from poorer hinterlands.

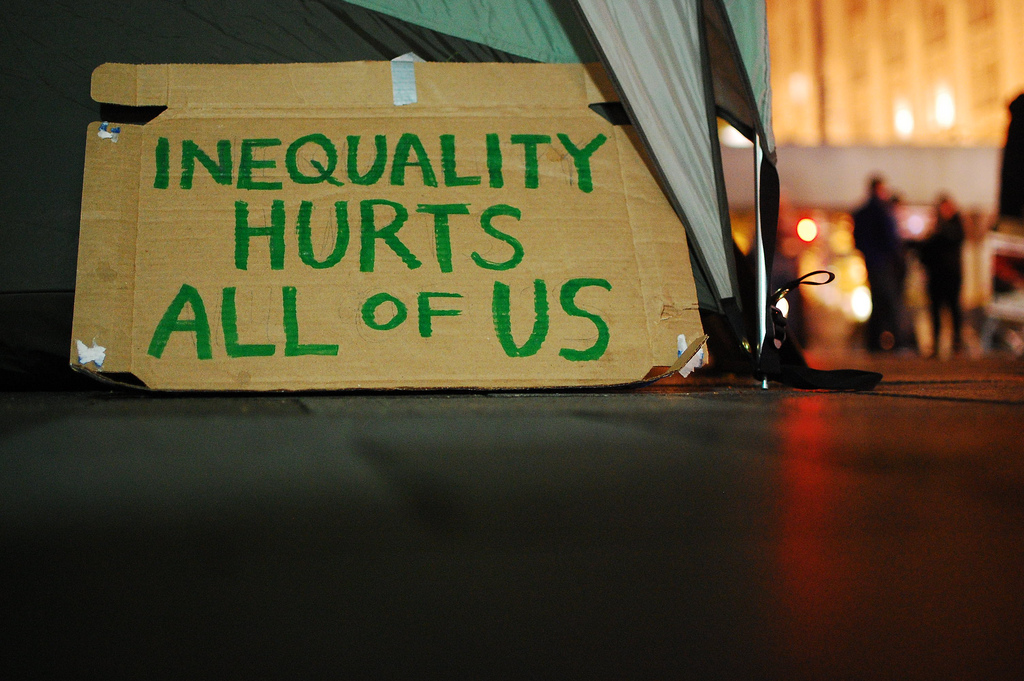

The result, in Europe, is the cry of pain from non-metropolitan areas – the “left behind” phenomenon in Britain, France and elsewhere. Britain’s regional inequality is extreme but not unique in Europe.

And then there is inequality in the US, with the Brandeis’ Child Opportunity Index finding whopping differences even within metro areas such as Detroit, Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Is it any wonder political disaffection in the US and Europe is so high?