Much ado about the Bard’s birth-day

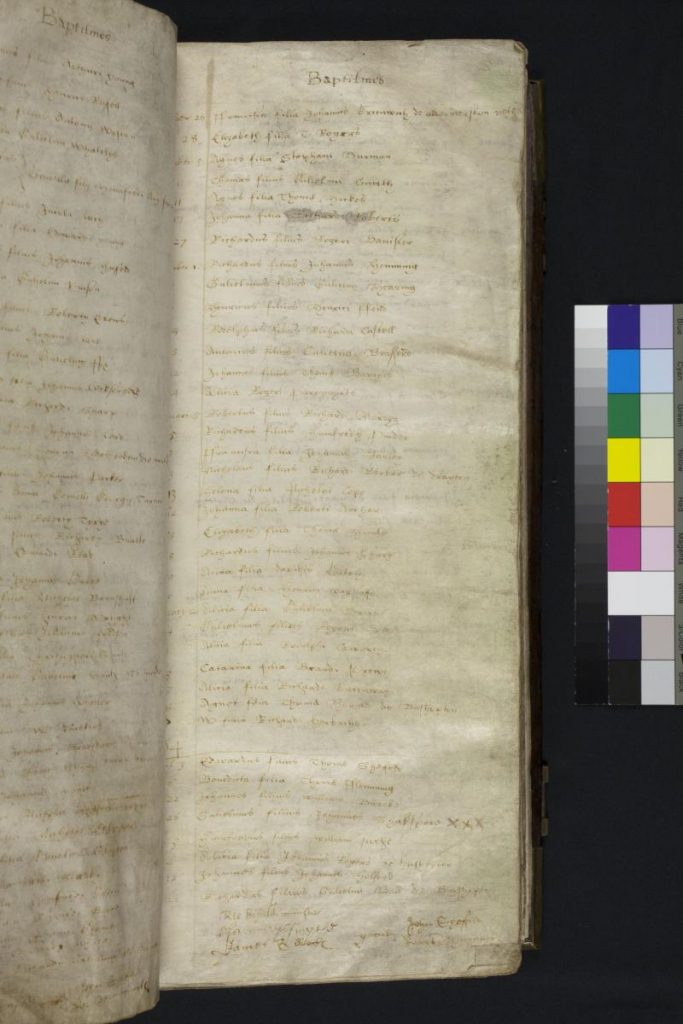

Reproduced by permission of Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 International license

/ TRAVELS IN MY MIND

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life”

– Jack Kerouac

April 23 was Shakespeare’s birthday.

Allegedly.

No one really knows because there aren’t any records of his birth. However, the Holy Trinity church in Stratford-upon-Avon apparently records his baptism on April 26, 1564. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust says this means a birthday no later than April 23 because “captisms typically took place within three days of a new arrival, and parents were instructed by the Prayer Book to ensure that their children were baptised no later than the first Sunday after birth.”

Holy Trinity church in 1918. Reproduced by permission of Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

Going by that logic, Shakespeare could’ve been born on any one of the following dates:

** April 26

** April 25

** April 24

** April 23

No one knows, but scholars and historians clearly went for decisiveness, thereby pleasing the marketeers no end.

At the end of the day, April 23 is better than saying “April 23 to April 26”. It has become an industry. Not just the annual Shakespeare birthday celebrations (no, really) in Stratford upon Avon – I attended in 2008 – and the tat. But also the way modern storytellers integrate April 23 into their narrative. Consider, in this regard, Paul Theroux’s 2019 piece in the London Review of Books (subscription). It’s about the geese he bought to keep down the grass in the meadow in front of his house on a remote Hawaiian island. What does any of this have to do with Shakespeare? And yet, he slips in a reference, noting when he saw the first duck egg hatch: “This was in 2008, on 23 April – Shakespeare’s birthday.”

Predictably, he names the first hatchling “Willy”. He describes his transformation as follows: “The first moving creature Willy saw was me, and he snuggled in my hand, and when I put him in a warm cage I kept it at eye level and made sure he had plenty to eat. He doubled in size in ten days, and within a month grew pinfeathers, and then fledged in earnest, spiky feathers that gave him bulk and turned him white. When I held him I could feel his pulsing heart, his warm body. And very soon, when I said, ‘Willy’, he responded with a little caw.”

Nothing to do with Shakespeare really, and yet, a link is made. The connection is forged through that date – April 23 – the Bard’s birthday. Allegedly.

Shakespeare would probably have approved. He had a lively imagination and a sense of the possible. Also, the birthday appears to have been taken very literally in Shakespeare’s day – as the actual day of birth. At the time, it wasn’t seen as an excuse for a party (or a pop-up souvenir shop). But it was still a big deal. Consider the three references to “birth-day” in Shakespeare’s plays:

“This is my birth-day; as this very day

Was Cassius born.” – ‘Julius Caesar’

“It is my birth-day:

I had thought to have held it poor: but, since my lord

Is Antony again, I will be Cleopatra.” –‘Antony and Cleopatra’

“Marry, sir, half a day’s journey: and I’ll tell

you, he hath a fair daughter, and to-morrow is her

birth-day; and there are princes and knights come

from all parts of the world to just and tourney for her love.” – ‘Pericles’