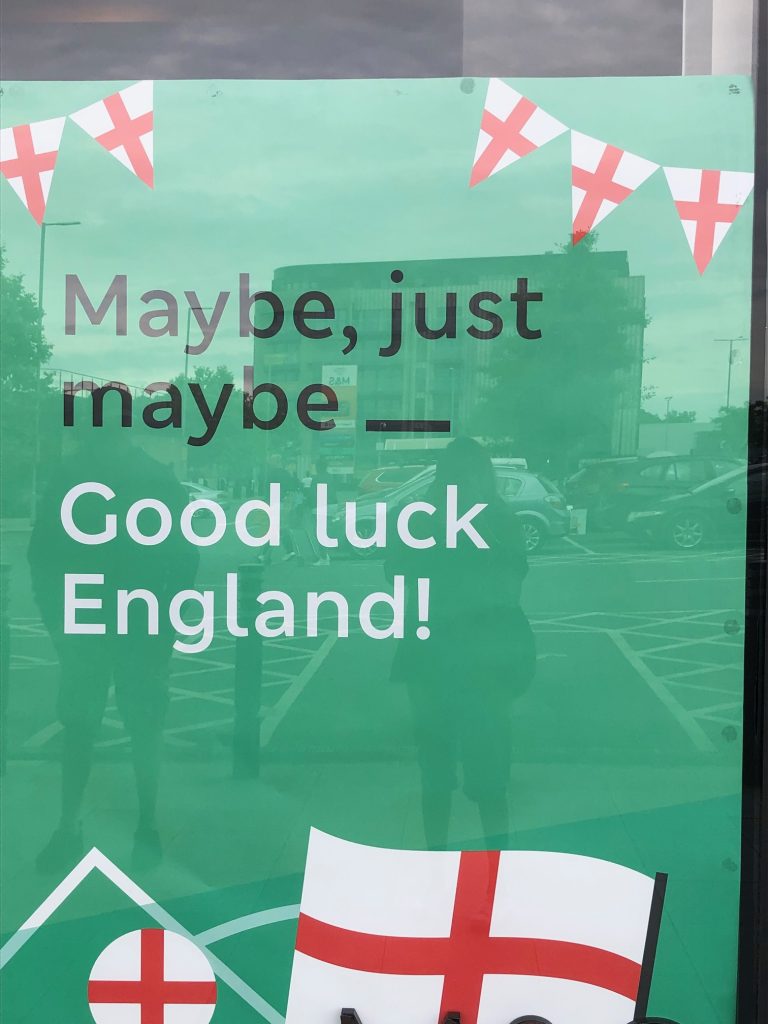

‘Maybe, just maybe_ Good luck England!’ Football and the art of understatement

Sign in a shop window in London the night before England play Italy in the Uefa Euro 2020 final on July 11, 2021. Photo: Rashmee Roshan Lall

/ TRAVELS IN MY MIND

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life”

– Jack Kerouac

Walking past a shop, I saw the sign in the window. “Maybe, just maybe_,” it said. And then, “Good luck England!” There was a flag with Saint George’s Cross and a bit of bunting with the same thing. And that’s it.

It was curiously moving in its understated hopefulness, as the England team prepared to play Italy on Sunday. Much of the nation yearns for England to win a major football tournament for the first time in 55 years. Much of the nation expresses the emotion almost exactly like that sign in the shop window. “Maybe, just maybe_ Good luck England!”

Is it to do with that peculiarly English trait — understatement — of which there are many humorous and overstated examples?

English understatement makes for good film and television. One oft-quoted ‘Monty Python’ scene captures it perfectly. Death shows up at a suburban dinner party wearing a long black cloak and bearing a scythe and a guest responds as follows: “Well, that’s cast rather a gloom over the evening, hasn’t it?”

There is, of course, the possibility that English understatement is a form of humble-brag. Perhaps it’s meant to emphasise a self-evident truth, ie superiority. Why belabour the point? Or, as the quintessential Englishman, Shakespeare wrote in ‘King John’:

“To gild refined gold, to paint the lily,

To throw a perfume on the violet,

To smooth the ice, or add another hue

Unto the rainbow, or with taper-light

To seek the beauteous eye of heaven to garnish,

Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.”

Interestingly, even someone as acutely perceptive as the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson rather believed in British exceptionalism (though he seemed a bit dubious about the Scots). In ‘English Traits’, his portrayal of 19th century England after visiting the country twice — in 1833 and in 1847 — Emerson wrote admiringly: “The practical common-sense of modern society, the utilitarian direction which labor, laws, opinion, religion, take, is the natural genius of the British mind”. However, he was rather hard on the country north of the border, saying that “In Scotland, there is a rapid loss of all grandeur of mien and manners; a provincial eagerness and acuteness appear…”

Emerson seems to be paying tribute to a certain kind of Britishness, one that won’t show itself as over-eager…even for a football triumph that would be a rare moment of shared national joy in the years after Brexit.

Maybe, just maybe.