Earlier this month, a missing teenage girl was rescued from a car in Kentucky when a passing driver noticed her making a hand gesture that has been popularised on TikTok as a signal of domestic distress.

This was the most high-profile instance of the hand signal’s successful use and has prompted hopeful commentary that the sharing of secret signals on social media could serve as a vital tool against domestic violence.

And so, on Thursday, the UN’s annual 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence kicked off with renewed hope. This year, the international campaign has a fresh focus on hand signals and how they can be used by women and girls in distress to seek – and gain – crucial help.

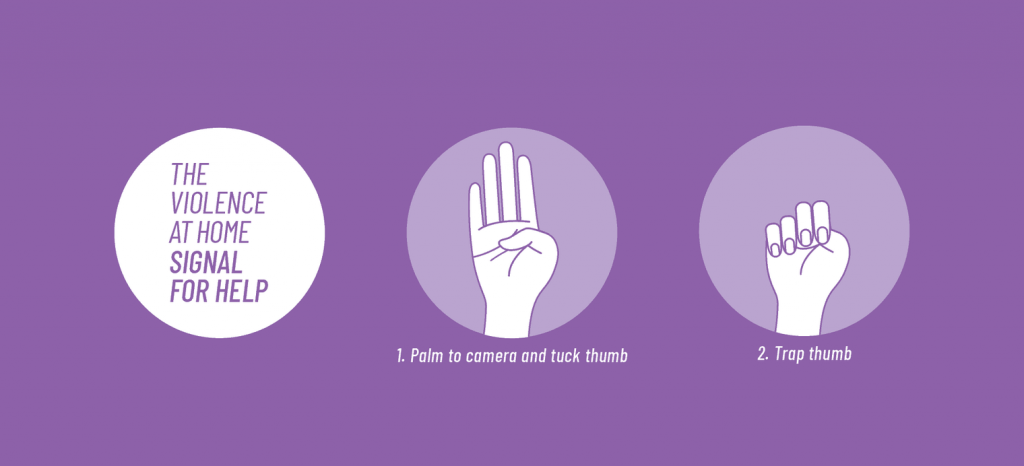

The Canadian Women’s Foundation, a non-profit that created the gesture used in the case in Kentucky, in the US – hand up, palm out with the thumb tucked in, and then fingers folded down – in April 2020 believes that signalling is important. To coincide with 16 Days, it has now compiled a guide for people who see the gesture.

Andrea Gunraj, the group’s vice-president of public engagement, told openDemocracy that the new “signal responder’s guide would ensure that people are well-equipped to respond and figure out what a person needs when they make that gesture”. The responses can vary, said Gunraj. “Sometimes, the person making the gesture just wants to tell someone what is happening; sometimes they may want help finding services such as a shelter.”

The UN’s Global Database on Violence against Women cites a 2013 review of available data that found 35% of women worldwide had experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence. Fewer than 40% of the women who experience violence seek help of any sort.

Accordingly, a lot of hope is being vested in secret signals.

Gunraj says the Canadian Women’s Foundation recognised that “ gender-based violence tends to spike in times of crisis” — in this case, the pandemic-induced lockdown. Intensive work alongside Toronto-based ad agency Juniper Park, which offered its services for free, led to the creation in April 2020 of a simple one-handed sign that was discreet, left no digital trace and did not overlap with words, letters or ideas in American Sign Language or any other sign language. “It was a post-#MeToo follow-up,” says Gunraj, “we were using technology to share something that is hidden and stigmatised.”

Coincidentally, that same April, a Polish teenager launched a fake online cosmetics shop ‘ Chamomile and Pansies’ for women to secretly ask for help if they are victims of domestic violence. When victims pretend to buy a product, specialists respond with questions such as “how long have the ‘skin problems’ been going on?” Women are also able to secretly contact psychologists and the police via the supposed purchase of skin cream. Like the hand signal from Canada, Krystyna Paszko’s idea, which has a Facebook page and won a European Union prize, was a direct response to the pandemic.

An evolving conversation

Domestic violence activists say the new signals have precedent. The 2015 Black Dot campaign had victims drawing a black dot on their hand to secretly indicate abuse. But clever new signals and fake online shops are one thing, recognising what they mean is quite another.

“Gestures are an important part of how we communicate and language is not just signals but the context we use it in,” Cat Hobaiter, a primatologist at the University of St Andrews, who studies communication and cognition in wild apes, told openDemocracy. In order for the domestic violence hand signal to be effective, she added, “it needs to be understood by the person receiving it.”

With one eye on that, the Canadian Women’s Foundation filmed the video that would later go viral on TikTok and reached out to international partners including the US-headquartered Women’s Funding Network (WFN) to ask them to share it.