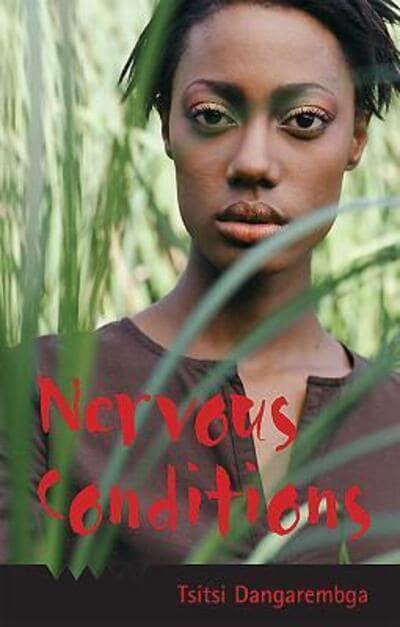

‘Nervous Conditions’ is about the lot of women…and more

The first line of Tsitsi Dangarembga’s novel ‘Nervous Conditions’ is not easy to forget:

“I was not sorry when my brother died”.

The unregretful person is Tambu, the poor, bright and striving daughter of a family in rural post-colonial Rhodesia of the 1960s. The death of Tambu’s brother – a lad who poked fun at the little girl and strutted, chest puffed out with male pride – gives her a boost. It allows Tambu to take her brother’s place at his all-fees-paid school and to live in comfort with relatives in the city. The rest of the plot follows on from there. There are some surprises but mostly, it is a familiar story of male privilege. And the disproportionate load heaved on to women. As Tambu’s mother tells her early on in the book, “The business of womanhood is a heavy burden”.

And as Tambu reflects some years later, as she goes from a peasant’s knowledge of the world to assured cosmopolitanism: “The victimization, I saw, was universal. It didn’t depend on poverty, on lack of education or on tradition. It didn’t depend on any of the things I had thought it depended on. Men took it everywhere with them. Even heroes like Babamukuru did it. And that was the problem. . . . all the conflicts came back to this question of femaleness. Femaleness as opposed and inferior to maleness.”

‘Nervous Conditions’ was the first English book published by a black Zimbabwean woman. At the time, 34 years ago, it was a clarion call – not just to women but to all who wanted to rebalance the structures of inequity.

A female, aspirational Zimbabwean writer of white ethnicity would later recall the way the novel hit her: “‘Nervous Conditions’ made clear that the systematic racism and sexism — the violent facts of my own white settler childhood in pre-independence Rhodesia — weren’t accidents but arrangements, structures that we’d all built together: the whites flogging the blacks, the near slave-labor wages.”

No, ‘Nervous Conditions’ is not just “women’s fiction” but it has a lot about the lot of women.

Also read:

https://www.rashmee.com/2022/08/01/the-joys-of-motherhood-and-the-womens-fiction-shelf/

https://www.rashmee.com/2022/07/31/two-great-examples-of-womens-fiction-show-the-need-to-level-up-literature-as-well-as-society/