Also read:

What this dargah in Landour, high up in the Garhwal Himalayas, says about Modi’s India

Enlarge

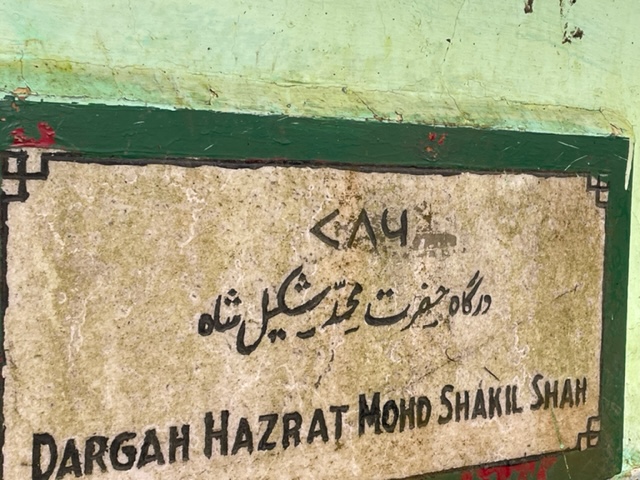

In Landour, high in the Garhwal Himalayas, sits a dargah or shrine of a Muslim saint. A stone plaque to one side announces that it is the “Dargah Hazrat Mohd Shakil Shah”. The structure is slight, with walls but six-feet high and a sloping corrugated steel roof. It’s a colour that’s a cross between mint and seafoam, so wall paint company palette sheets tell us. Peer through the bars of the locked gate and you see an immense, twisting tree trunk pushing itself out of the earth, from which hang disparate objects – a green scarf with a golden fringe; an array of threads; a metal pitcher with a long thin spout.

It’s easy to imagine the dargah as a place of mystery. A child would look through the bars, probably see a dragon’s tail peeking round the corner of the tree trunk and embark on a mindspassage that traverses worlds yet unseen.

For an adult too in 21st century India, this small dargah, right outside a B&B called La Villa Bethany, in this small hill station is equally liable to trigger a journey into spaces as yet unexplored. (This earlier blog explains the meaning of the term ‘hill station’.)

Some might say it’s incredible that the dargah is intact, green and unsullied, matching almost exactly the foliage of this lovely part of the Garhwal Himalayas. For, this is a time of peril for the idea of a secular India, the notion of inclusive nationhood enshrined in the constitution having decayed. Politicians belonging to the Hindu nationalist governing BJP constantly invoke the right of Hindus to “practise their faith” and challenge any attempt by the country’s 200 million Muslims – the world’s biggest religious minority – to overtly indicate their presence.

The dominant sense, as ‘The Economist’ recently described it, is of Hindu-nationalist dogma filtering “into mainstream discourse by a slow-drip process. This has been propagated by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or RSS, a volunteer service corps founded in 1925 and once regarded by many Indians as cranks. Myriad affiliated groups (including the BJP) with tens of millions of members, amplify the word. Their main message, that Hindus must unite to face imminent danger…” Hindu consolidation is promoted by pointing to “a common enemy—generally Muslims” and it is mostly, electoral magic.

There is, of course, all of that. But what then of the Landour dargah? Why is it still there, all fine and dandy in its minty gloom?

The truth is India isn’t erasing everything that’s discernibly non-Hindu, just the bits that matter the most.

Like the Babri Mosque, a 16th-century structure, which was said to be built on the site of the god Ram’s birth in the northern town of Ayodhya.

Like the right to expect equal protection from mob violence.

This little dargah, high up in the hills of northern India, is probably just too insignificant to bother much about.

It’s good it’s still there. Until it’s not.