Port au Prince: The city liveability index probably just won’t work here

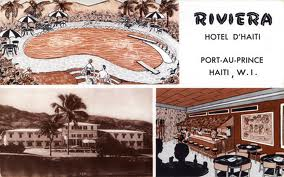

A 1950’s postcard from Riviera Hotel d’Haiti, Port Au Prince, from the time the city is often described as very pleasant and liveable

Everyone always tells me about Port au Prince’s liveability “back then”, before the earthquake, before the Troubles, before everything fell apart. But surely that was the era that followed on from the period described by Graham Greene’s ‘The Comedians’? He set the novel in the darkest days of the dictatorship of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. Later, Port au Prince would be at its most “fun” in a Club Med, frolicsome way, under his son and heir, “Baby Doc“.

It is a troubling thought that Port au Prince may have been at its best in the age of total control. Does a city’s liveability have only a small moral compass?

It’s a point worth considering now that Bloomberg’s reporting a remarkable rise in home prices in 20 US cities. The year-over-year gain since 2006 is led by Las Vegas and followed by San Francisco. Atlanta and Miami feature too. It’s described as a “solid recovery” for the US housing market and a harbinger of rising consumer spending, off the back of a feelgood sense that you’re worth more just because your home is.

Though the ‘housing wealth effect’, as it’s sometimes called, can give a city considerable clout, you’ve got to wonder if it all really adds up. Why would house prices rise 27.3 per cent in a gaming capital like Las Vegas, for instance, but just 23.2 per cent in beautiful San Francisco? Supply and demand? Some convoluted aspect of some arcane desirability index? As per some weird logic of the market? Was a house in Papa Doc’s Port au Prince more desirable than in President Martelly’s in 2014?

It’s always hard to measure cities – and how they should be ranked. Should liveability be the lead factor? If so, who for? People who live there all the time; half the time; or for a limited period? Who judges what makes a city liveable? Someone who’s lived there always? Or might it be better assessed by people who’ve moved around so much they have many other cities to compare with?

Last Fall, The Economist was criticized for naming Melbourne the world’s most liveable city for the third year in a row. Paul James, director of the Global Cities Institute and Director of the UN Global Compact Cities Programme at RMIT University, pointed out, that the index seemed generally angled at expats, more particularly their companies, which “have to consider the hardship ratios of different cities in working out how much salary loading they deserve.”

He added, with acid emphasis, “Melbourne is not the world’s most liveable city. It simply means that on a series of indicators that measure lifestyle, Melbourne is pretty good. It has a wonderful mediocrity across the broad range of indicators have been chosen by the good people at the Economist, and it is marginally ahead of the other top 100 cities.”

He’s probably got a point but one has to wonder what would constitute a better index than the five categories used: stability, health care, culture and environment, education, and infrastructure? Mr James is sniffy about the whole thing but surely it can only be good (if slightly boring) to live in, what he dismisses as a “politically stable city with minimal crime, a basic publicly funded health system and good quality private education”?