Iraq. Bangladesh…Are some countries second-class triggers of global grief?

Some countries are second-class triggers of global grief. It’s true, for all that we pretend to care equally about everyone all the time.

Anne Barnard, The New York Times’s Beirut bureau chief, recently wrote about some people’s outrage that there was insufficient global outrage about last week’s deaths in Iraq, Turkey, Bangladesh and Saudi Arabia. Those deaths at the hands of terrorists didn’t trigger collective planet-wide mourning, they complained.

She was presumably describing the anger felt by people with whom she interacts on her beat, which is to say Syrians in Syria and elsewhere, Lebanese and others in Lebanon and some other parts of the Middle East.

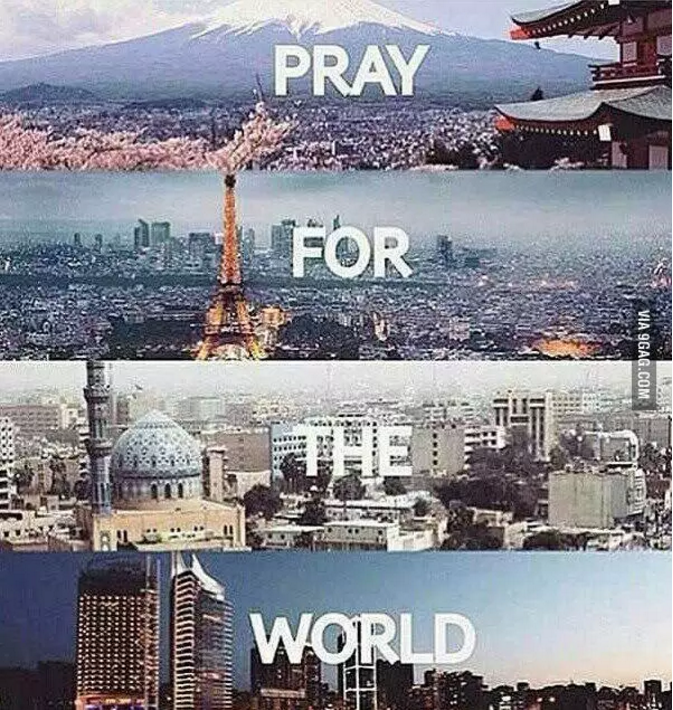

They wondered, she wrote, why there weren’t trending hashtags (#PrayForIraq, for instance) as for France and Belgium in their moment of pain.

Why were people’s Facebook profiles not stiff with the sympathetic virtual fluttering of Turkish, Bangladeshi, Iraqi and Saudi flags?

Why were the Eiffel Tower and other iconic European structures not lit in the flag colours of the country most recently attacked by jihadis?

Is there a right answer to these questions? Almost any answer will be deemed offensive or insufficiently empathetic. But there are some basic, if dismal, points to keep in mind:

** France and Belgium are not in the same state of conflict-ridden disarray as Iraq. Unfortunately, bad news from Iraq seems less surprising than from Europe.

** Turkey does not prompt the world to identify with it in the way of many other countries. So too Saudi Arabia. In the case of Turkey, this is largely because of its increasingly erratic president, his administration’s crackdowns on free expression and the Establishment’s somewhat blinkered approach towards the Kurds. As for Saudi culture, it seems far too foreign and unfathomable to many beyond its borders. As Marco Iacoboni, a psychiatry professor at UCLA, wisely explains, “We tend to empathize more with people that we feel are more ‘like us’. ”

** Bangladesh has had a bloody running story in the last few years, one that has largely been left unexplained to the wider world. That story has involved murderous attacks on secular bloggers. With each gruesome incident and each seemingly phlegmatic Establishment response, an unfortunate impression has grown. It is as follows: That the country’s gentle culture of moderation has hardened into a radically violent form of Islam and that most Bangladeshis support this. This is not accurate but failing to challenge the perception has allowed it to seem so.

There is another reason too that some countries seem to serve as second-class triggers of global grief. Their political leaders don’t champion their case empathetically. They neither explain their people’s situation, nor the depths of their sorrow over a tragic event. Do these leaders not care? Or do they not care enough?

We have been here before. In January 2015 to be precise. In the same week as the Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, more than 2000 Nigerians were killed by Boko Haram militants. The world focused on Paris, not Baga. Allegations of a cruel Western hierarchy of grief spread faster than the tweeting of a hundred-thousand trolls.

Was the world’s focus on Paris rather than Baga because of a West Vs The Rest double standard of measuring grief?

Was it at least partly the result of the manifest silence and unconcern of the African press and political class? For, African leaders and media paid little attention to Nigeria’s tragedy. Even Nigeria’s then president, Goodluck Jonathan, took care to express his condolences for the victims in France but stayed silent on the Boko Haram attacks. So too his finance minister. The Nigerian president even reportedly attended a family wedding that horrific weekend.

For Mr Jonathan, it may have been politically expedient to ignore a terrorist group that had only grown in prominence on his watch. It is the same sort of callous calculation that often marks the reaction to violence in some parts of the Muslim world. When conflict is sectarian in nature, the press, political and public reaction comes through as coloured – stained with bias.

As with the Nigerian President’s non-response to the massacre of his people, muted reactions to sectarian attacks can signal a lack of sympathy for one’s own people.

Unfortunately, this chimes with the angry realism often heard in populous parts of the developing world: life is cheap here; it just isn’t valued the way it is in the West.