These short stories make true the saying ‘Cairo writes, Beirut prints, Khartoum reads’

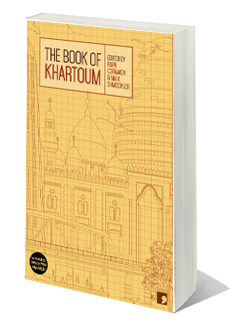

I’m reading ‘The Book of Khartoum‘, which is apparently the first major collection of stories on the Sudanese capital to be translated into English, and this is how it starts:

I’m reading ‘The Book of Khartoum‘, which is apparently the first major collection of stories on the Sudanese capital to be translated into English, and this is how it starts:

With a story titled ‘The Tank’.

With the writer Ahmed Al Malik describing – sardonically, searingly – how a Sudanese householder might conceivably buy a tank (just as one would a car, carefully checking its registration papers and state of health.) “The sight of it (the tank) parked under the neem tree in front of our house did come as a shock to a few of my friends”, writes Mr Al Malik, acknowledging that his daughter’s English tutor also ceases to show up, the milkman is in a panic and confesses to watering down his wares and even his father’s debtors arrive with many apologies but not the actual cash.

This is the way it goes in ‘The Book of Khartoum’, stories in which the city is a character – a deeply affecting, vulnerable, exasperating and glorious entity. In some ways, the collection makes true once again the Arabic saying: Cairo writes, Beirut prints, Khartoum writes.

Poet Ian Pople, who teaches academic literacies at the University of Manchester, reviews ‘The Book of Khartoum’ as follows: “The stories move within a kind of Sudanese magic realism.” And he correctly places them within the context opened up by British Sudanese writer Leila Aboulela, who writes in English. I’ve read her work and can attest that ‘The Minaret’, for instance, sparked a desire to read and know more about Sudan.

Largely though, as Mr Pople says, Sudanese literature is hardly known to English readers. He mentions El Tayib Saleh’s ‘Season of Migration to the North’, which I haven’t read.

‘The Book of Khartoum’ goes some way towards filling that gap.