Oil prices don’t really tell us much any more about the state of war or peace

By SpLoT, Sudopeople

On January 3, oil prices spiked after Iran’s top general, Qassem Soleimani, was killed in a US airstrike at Baghdad’s airport on the orders of President Donald Trump. That they were near their highest level since mid-September, when attacks in Saudi Arabia took out a chunk of the kingdom’s production capacity said a great deal. It was a reflection of fears about the escalating tensions between Washington and Tehran. The question being asked early on January 3 was as follows: What will happen to the crude that flows through the Middle East? Will the spigot be turned off?

Another question seems to have been asked in the hours since: Will it matter if the oil flow is disrupted?

That’s obvious from the fact that the rise rise in oil prices has subsequently been somewhat muted. This suggested that investors expected the reaction to Soleimani’s killing to be contained, said Adnan Mazarei, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics and former deputy director for the Middle East at the International Monetary Fund.

Sure. But what about crude flows through the Middle East?

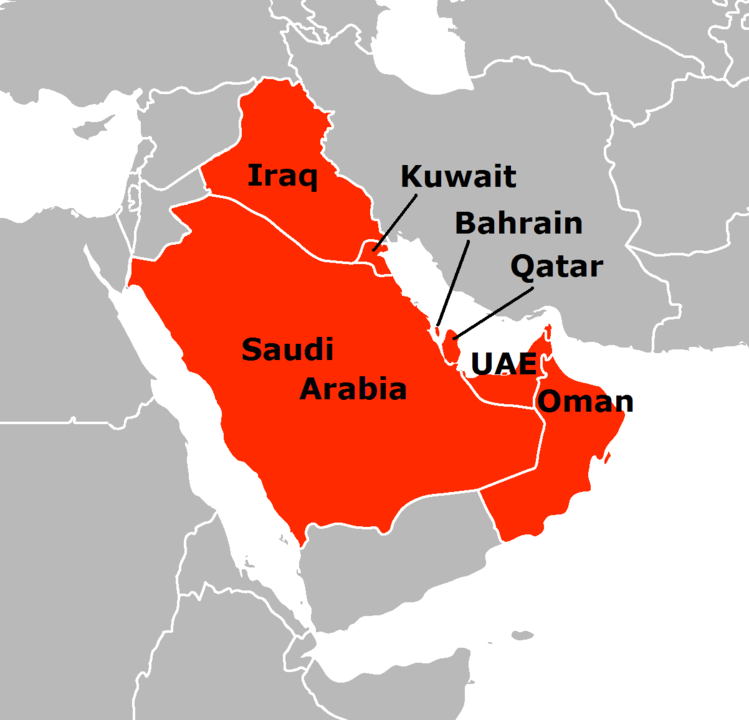

The US is now the world’s largest crude producer and North American fracking has meant a glut of oil. The world is much less reliant now on Middle Eastern oil than before. Opec, the cartel of mainly Middle Eastern countries which used to control much of the supply of oil, no longer has the same sway. And there is also (the admittedly lower-volume but still significant) share of renewable sources of fuel on the market.

There will be ripple effects of a US-Iran conflict simply because of the amount of crude that flows through the Middle East and because Saudi Arabia is still the globe’s dominant exporter.

But oil prices really do not, any longer, indicate the likelihood, form, intensity or spread of a hot conflict.