Does the centre-left have the ideological flexibility to take power?

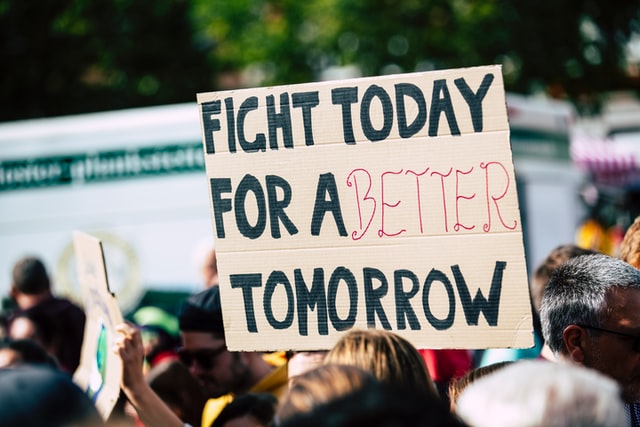

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

In the days before the coronavirus epidemic struck, there was a growing sense that the centre-left in the US and UK was no longer ready for change, that it was too broad-minded, as poet Robert Frost once said, to take its own side in an argument.

The pandemic is changing things. Ideas normally considered socialist and left-wing are now increasingly considered essential.

In the UK, for instance, the governing Conservative Party is deploying the full force of the state to underwrite the British economy, which means the economic arguments that have long preoccupied the left are suddenly suspended. Even so, the centre-right and right do still gag a bit at some of the left’s principled insistence on taking care of the most vulnerable in society.

In the US, there was a Congressional struggle over the deal on coronavirus fiscal stimulus measures worth nearly $2tn. Democrats on Capitol Hill lamented that the proposed deal offered big business an overly generous bailout with limited conditions and scant oversight. They also argued it would not release enough new funds to hospitals.

The deal was eventually done but the wrangling revealed a great deal about the knee-jerk response from both left and right even in the face of a pandemic.

So, despite the change because of the pandemic, it’s still worth thinking about the left’s particular worldview. It is distinct, often prompting complaints about an allegedly misplaced fidelity to principle over pragmatism.

Here’s a pre-coronavirus example. The left, for the most part, will not spin (falsely and with vicious fervour) when it blunders.

For example, the chaos at the February 3 Iowa caucuses (that sounds almost as if it were another age, which it was.) After the caucuses’ organisational debacle, the Democratic Party didn’t try to excuse itself in any way. It come across instead as aghast, contrite, anxious to do better. It also, unwittingly, allowed the impression of incompetence to grow and grow.

Though this is a hypothetical case, it’s possible that if the Republican Party had overseen a similar fiasco of a primary election, it would have adopted a very different response. There would’ve been no honest bewilderment, no mea culpa, no promise to do better next time. Accordingly, there wouldn’t have been the impression of incompetence either.

Those very different approaches have long been on display in both parties’ treatment of allegations of sexual misconduct.

When Leeann Tweeden, a conservative talk-radio host, alleged in a 2017 blog post and a radio interview that Democratic senator Al Franken forcibly kissed her on a 2006 USO tour, Democrats began to call for him to step down. He did.

As for the Republicans, they allowed Donald Trump to be their nominee for president, have backed him solidly in the past three-and-a-half years, and on February 4, chanted “four more years” during the State of the Union address. This, despite the reality that Trump’s lascivious boasts of sexual predation are available in his own voice. And the fact that at least 23 women have, since the 1980s, accused Trump of rape, sexual assault, and sexual harassment, including non-consensual kissing or groping.

And then there was Alabama, December 2017. The Republican candidate for the Senate, Roy Moore, was accused by more than half a dozen women of predatory behaviour when they were teenagers and he was in his 30s. He lost to Democrat Doug Jones, but that’s not the point.

There are many other examples but suffice it to say when Democrats screw up, they seem more willing to ‘fess up than Republicans.

So when it’s said that the left is just not pragmatic enough, what that probably means is as follows: it generally tries to put principle above the need to simply win office.

That’s true both before and after the pandemic hit.