Labour unions are back in the spotlight in the US and for all the right reasons. There are implications for organised workers’ movements everywhere, as well as for the call to rebalance the deepening divide between labour and capital.

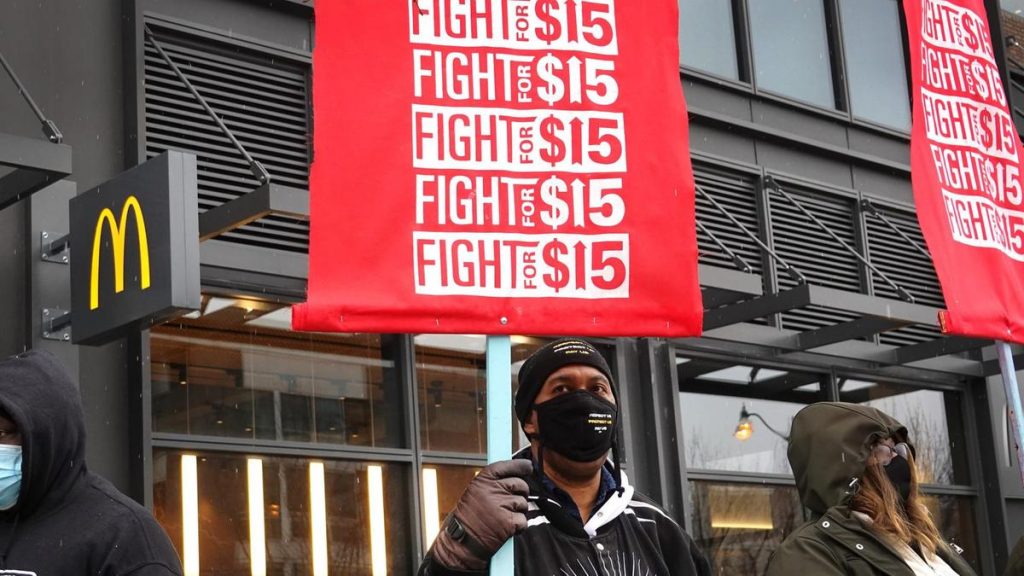

The resurgence goes beyond the obvious signals from America’s new administration. President Joe Biden has conspicuously placed a bust of the Latino labour activist Cesar Chavez in his office. This week, Marty Walsh, the former construction union leader he nominated for labour secretary, faces US Senate questioning on his suitability for office. And Janet Yellen, Mr Biden’s Treasury Secretary, has already told the Senate at her confirmation hearing that she wants to help American workers. Meanwhile, Mr Biden is pushing plans to raise the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, something that last happened in America in 2009. (It went from a measly $6.55 an hour to an unspectacular $7.25.)

Add to that Mr Biden’s unambiguous statement to the heads of some of America’s biggest companies in mid-November, days after the presidential election was called. He said: “Unions are going to have increased power [in his administration]. I want you to know I’m a union guy — that’s not anti-business.”

It seems like a good moment to wax faintly poetic when posing a number of prosaic questions.

Will the dignity of work, rather than wealth, be recognised once more in America? Will Americans in full-time work now earn a living wage after 40 years of hard scrabble? Will organised labour really be able to diminish organised greed? Will the essential workers being saluted by everyone everywhere during this global pandemic finally get their due? This category includes people precariously situated within the gig economy, such as Uber and food delivery drivers, as well as low-paid, full-time workers such as nurses, supermarket shelf-stackers, cleaners and bus and train drivers. And finally, is a business model that only seeks profit no longer fit for purpose?

There are signs that change is brewing, even far away from Washington. Amazon, America’s second-largest private employer, is fighting the very first attempt by its US warehouse workers to unionise. Chances are the mail-in ballots will go through in a week’s time.

Just days ago, Google workers said they would form a global union alliance, the domino effect perhaps of their fellow employees at Alphabet, Google’s parent company, forming a labour union for US and Canadian offices. It is significant if only as a cultural marker and could theoretically be a template for workers at other tech giants in offices and warehouses around the globe.

In late January, the US Supreme Court announced that it would not hear a group of cases that threatened to impose dire financial penalties on public sector unions, which would have straitened their ability to act.

Encouragingly, a Gallup opinion poll from September estimated that 65 per cent the American public — a figure that includes 45 per cent of all Republicans — approves of labour unions. And new data from the US Bureau of Labour Statistics shows that union membership within America’s overall workforce has risen for the first time since 2008 in percentage terms.

That last statistic may be more telling than anything else. In 2020, American labour unions didn’t sign up more workers. But so many non-unionised workers were laid off in the year of the pandemic that it led to an increase in the proportion of unionised workers.

This indicates a manifest lack of protection for non-unionised labour and has created a new energy to mobilise and change the status quo. Workers’ wages and benefits have been declining since the 1980s in the US and in other developed countries, almost in sync with falling union membership. In the UK, for instance, 23.4 per cent of workers were part of a union in 2018, half the 1979 peak. But the pendulum is starting to swing back in some countries, with researchers at Massachusetts Institute of Technology reporting in 2018 that roughly 48 per cent of America’s non-union workers would join a union if they could.

So, what happens next?

There is a very real chance that the US Congress, which is narrowly controlled by Mr Biden’s Democratic Party, will swing into action. The federal minimum wage may rise and Congress may pass into law the Protecting the Right to Organise Act.

The PRO Act is significant because it reverses decades of laws and regulations that have increased the bargaining power of employers to the detriment of workers, allowed wages to stagnate, income inequality to soar and giant corporations to have undue sway over politics and policymaking. Steven Greenhouse, who explored these subjects in his 2019 book Beaten Down, Worked Up: The Past, Present, and Future of American Labour, believes that worker power can only be rebuilt by making it easier to unionise.

The implication is clear. Active, and more to the point, respected labour unions should be allowed to restore balance to the capitalist system, protecting the rights of those who work, as well as the fortunes of those who pay them to do so. A happy workforce should, in theory, be a win for management because it boosts productivity.

Giving workers a better deal would align perfectly with all the talk of corporate social responsibility

Of course, any change in workers’ prospects in the US would still be very different from Germany’s famously consensual co-determination system of company management. The German model has a “works council” made up of trade union members, which participates in decision-making alongside the firm’s executives. The unions look out for their members while also keeping an eye on the company’s balance sheet. But attempts by the German carmaker Volkswagen to transplant the system to its factory in Chattanooga, Tennessee a decade ago didn’t work. The state’s politicians were hostile and the plan was ditched.

That was then. Might things be different in 2021? After all, there have been signs that big business is minded to embrace a more inclusive model of capitalism. In 2019, leaders of the influential US-based Business Roundtable declared that firms should serve stakeholders as well as shareholders. It was a significant shift in the guiding philosophy from economist Milton Friedman’s 1970 argument that business has only one responsibility — to increase its profits.

Giving workers a better deal would align perfectly with all the talk of corporate social responsibility.

Rashmee Roshan Lall is a columnist for The National