Glorious myths about the Alamo ‘sacred shine’ draw millions every year

In the origin story of Texas and the United States, it's more than a building

We arrived in the lovely city of San Antonio, Texas, just yards from the Alamo, the morning after the iconic monument’s footprint was expanded.

With that broader footprint comes a deeper, possibly more troubling narrative. Troubling as in heedless, deliberately careless of what really happened at the Alamo and what its real story is.

Let me explain. The Alamo is more than just a building in the origin story of the state of Texas as well as the United States.

It is the living history of San Antonio, of Texas, and of the United States. It symbolises centuries of European colonisation, Texan self-determination and American expansion into territories formerly colonised by a European power and then a North American one.

After I lay out the basics of the Alamo, I will come to why it now tells an incomplete but thrilling Anglo-centric tale that has become legend but is discordant in an age that is seeking decolonisation (of mores, mind and history).

The basics are as follows. The Alamo is an 18th century Franciscan mission. Once a chapel, it was established in Spanish Texas by Roman Catholic proselytisers on the border of Spain’s vast North American empire. It later became a fort and was used by the armies of four political entities. First, Spain. Then Mexico, after it won independence from Spain. Then the Republic of Texas, which became an independent country in 1836 after pluckily resisting the overbearing rule of Mexico’s President General Antonio López de Santa Anna. Finally, the United States, whose Congress admitted Texas to the union in December 1845.

The Alamo, every history book will tell you, was the site of a historic resistance effort by a small group of less than 200 determined fighters for Texan independence from Mexico. Davy Crockett, American folk hero, frontiersman, soldier and politician, who is often referred to in popular culture as “King of the Wild Frontier”, died at the Alamo.

The story of the 13 days of resistance is a glorious one and the Alamo is one of the most popular historic sites in the United States. More than 2.5 million people visit the Alamo every year to hear about its place as a “sacred shrine” (as a film at two spots on the site reverentially intone), as the cradle of Texas liberty and America’s love of freedom and justice.

As a shining symbol of courage, the Alamo has contributed much to the American story. The battle cry “Remember the Alamo” was used by US soldiers when fighting Mexico during the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.

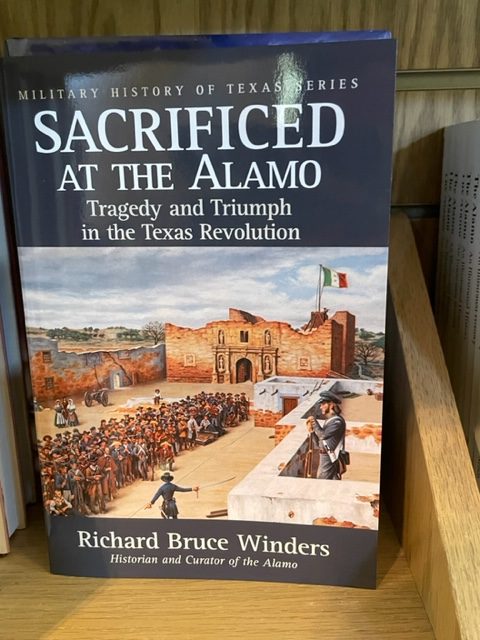

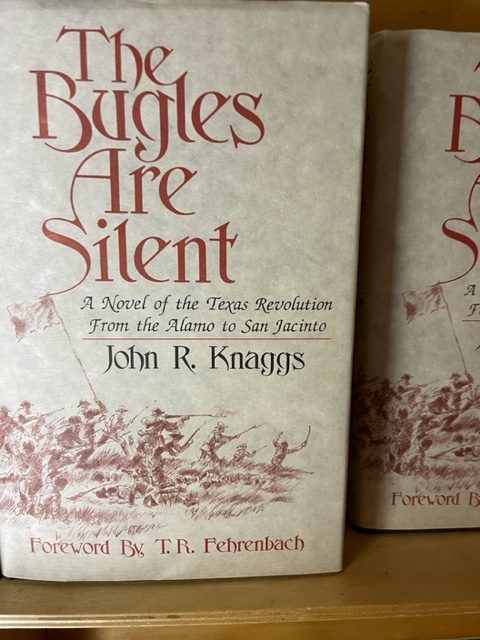

The Alamo has been commemorated in every way possible. It is on postage stamps, in books, in a Walt Disney series, in the hugely popular 1960 film John Wayne film and in all sorts of memorabilia veering towards tat.

It is now part of an ambitious plan for a historical recreation of the site’s footprint back during those 13 days of resistance. On May 24, the day before we arrived, the Alamo officially allowed visitors a sneak peek at the complex’s newest structure – the mission gate and lunette, a protective structure at its outer perimeter.

Funded partly by a $3 million donation from the Joan and Herb Kelleher Charitable Foundation, the gate and the lunette are meant to give people a broader understanding of the precise scale of the challenge faced by the Alamo’s heroic defenders. The gate and lunette recreation project are expected to be completed next year.

Unfortunately, the usual narrative about the siege of the Alamo ignores a key fact: it was about maintaining Texan cotton farmers’ right to have slaves as much as a fight against the autocratic Santa Anna.

We’ll look at that next.

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life”

– Jack Kerouac