America’s most trusted dictionary will redefine racism

Photo: Rashmee Roshan Lall

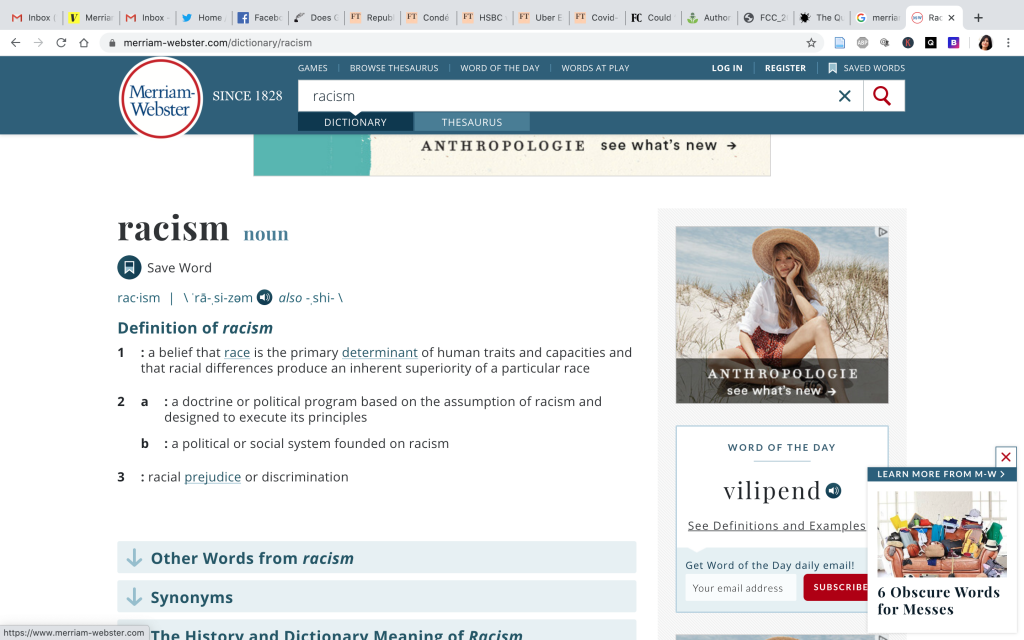

Merriam-Webster has been in the business of word definitions for the better part of 200 years. Now, in a nod to the changing national and international discourse, America’s most trusted online dictionary plans to revise its entry on racism . Merriam-Webster will now acknowledge that racism is systemic.

One of the dictionary’s editors has admitted: “Omitting any mention of the systemic aspects of racism promotes a certain viewpoint in itself. It also does a disservice to readers of all races.”

The change was suggested by Kennedy Mitchum, a black woman from Iowa who recently graduated from university. Mitchum, who had encountered people pointing to Mirriam-Webster to prove they weren’t racist, felt the dictionary definition needed to reflect broader issues of racial inequality in society.

After an email exchange, Mirriam-Webster agreed.

National conversation

Peter Sokolowski, an editor at large, noted public requests for revisions often coincide with the national conversation. For instance, Mirriam-Webster’s entry on marriage no longer contains references to gender. “Activism doesn’t change the dictionary,” Sokolowski said. “Activism changes the language.”

That’s true enough but does a dictionary definition really change much? Can it affect the reality — and practice — of racism?

Racial inequality in America has long rested on two plinths. One was legal and mostly came down with the end of slavery and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The law prevents employment discrimination on the basis of race and the racial segregation of schools and public housing. In the span of half a century, it’s fair to say the Civil Rights Act has shifted the organic lived meaning of racism.

Racial prejudice

But it is the second pillar of the structure — psychological support for biasagainst non-white people — that continues to inform the attitude of some and makes for racial prejudice, sometimes to brutal effect.

Unconscious racial bias was studied by Harvard University psychologists Tessa Charlesworth and Mahzarin Banaji last year. They published an analysis of 4.4 million results from an online test of Americans’ biases. The test, which is called an implicit-association test (IAT), scored biases based on how quickly a person associates black and white faces with nouns such as “good” and “bad” or “joyful” and “evil”.

The scholars found implicit biases based on race had decreased about 17 per cent in a decade and explicit biases had declined by more than twice that number (37 per cent).

It was a heartening conclusion except in one respect. The study showed racial biases still exist and are often reflected in such mundane actions as agreeing with the statement: “I think black people are lazier than whites.”

Hidden beliefs

Such attitudes, which are made up of explicit biases and hidden beliefs, inform deeper societal reactions and systemic responses. For instance, they can cause police officers to deal differently with black men than with white men.

It is in this context that Mirriam-Webster’s decision to revise its entry for racism is significant. After all, a dictionary helps define what we’re talking about so we’re all on the same page.

Originally published at https://www.thefocus.news