As Sri Lanka has shown, the world economy is in for a Micawberesque period

Enlarge

Public domain

In this decade, we’ve seen five countries go bankrupt, or pretty much bankrupt for all practical purposes. Greece. Lebanon. Zambia. Suriname. Sri Lanka.

Meanwhile, Tunisia and Pakistan are being closely watched. Their status is that of patients in intensive care.

Tunisia’s public debt has more than doubled from 39 per cent of GDP in 2010, and the government is forced to shell out large sums to service that debt, prompting concerns that Tunisia will go the way of Lebanon and default. Pakistan got a $6 billion bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on July 14 to avoid default.

As the pandemic slowly makes its way into the world’s rearview mirror, many emerging markets face a combination of high debt, low currency reserves, falling revenue and rising prices.

Sri Lanka epitomises this. The 2009 end of its civil war propelled it to the front of the line for cheap loans. It was, some say, an era of growth, a Great Gatsby-esque period of promises and parties. Mahinda Rajapaksa, then president, cut taxes.

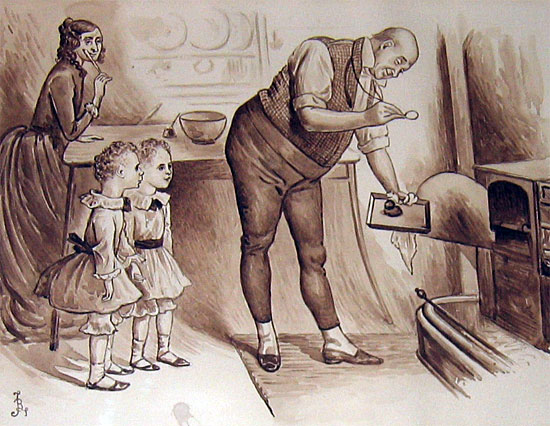

(As it turns out, it was less the Great Gatsby than Wilkins Micawber, Dickens’ poor optimist character in David Copperfield. Mr Micawber, remember, was incarcerated in debtors’ prison for failing to pay his dues.)

Anyway, then came Sri Lanka’s Easter bombings in 2019. The country’s crucial tourism sector suffered. In 2020, the pandemic further savaged tourism and the government started to run out of money. All those loans started to weigh heavily on the country. The Sri Lankan rupee’s value halved and prices spiralled. In April, Sri Lanka defaulted on its debt payments.

This may increasingly become the international picture. According to Bloomberg, about a fifth of the $1.4 trillion debt emerging markets countries owe to foreign bondholders is regarded as distressed. That basically means creditors wonder if they will ever get repaid.

The world economy is in for a Micawberesque period.