China brings its Belt and Road Initiative to Italy, paving the way for the Xin World Order

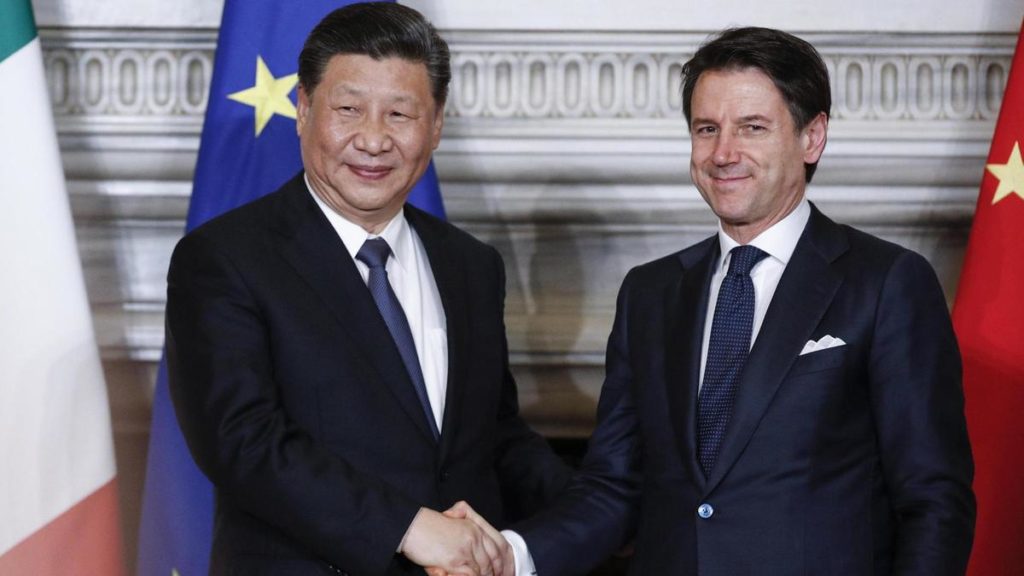

Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte shakes hands with the Chinese president Xi Jinping during a recent meeting in Rome. EPA

As the US turns in on itself, China is increasingly enthusiastic about engaging with and investing in the wider world

Once upon a time, the port city of Trieste represented a solution of sorts for territorial disputes between countries. Young Indians, for instance, learnt in political science classes about it as a possible model for Kashmir. After the Second World War, Trieste became an autonomous region between Italy and the former Yugoslavia, by UN charter. Although that arrangement lasted less than a decade, it seemed to offer proof that even difficult problems can be resolved peacefully, for a time.

Now, it seems that Trieste represents something else. It is a symbol of a global realignment, which could be called the Xin World Order (“xin”, pronounced “hin”, is Mandarin for new).

With Italy having become the first Group of Seven nation to participate in China’s vast Belt and Road Initiative infrastructure project, cities such as Trieste are set to become glad recipients of Chinese investment. Along with ports such as Genoa and Palermo, Trieste can expect to benefit mightily from Italy’s new arrangement with China. Officials in Trieste expect Beijing-backed conglomerates, such as the China Communications Construction Company, to bid hundreds of millions of euros for infrastructure concessions. After the Second World War, the Americans were prominent in Trieste. Now, the Chinese are increasingly in evidence — a presence that can only grow.

There is the glittering prospect of local jobs, paid for by Chinese companies working with Italian counterparts. And as another European state, Monaco is hoping, the Chinese luxury tourism market is also to play for. Xi Jingping was in Monaco on Sunday — the first state visit to the tiny, wealthy principality by a Chinese president — and in Italy the day before. Twitter users, many of whose names were in Chinese characters, hashtagged the cordial nature of both stops on Mr Xi’s European tour “Xiplomacy”.

That may be a tad overstated, but the mood with respect to China in Italy and Monaco is warmly positive. It is of a piece with the reception China has enjoyed in central and eastern Europe for some years, formalised in 2012 with the annual 16+1 summits, which feature 11 European Union member states and five Balkan countries. And China’s relationship with the EU as a whole appears to be ticking along nicely. The European Commission acknowledges that “China and Europe trade on average over €1 billion a day… the EU is China’s biggest trading partner, and China is the EU’s second biggest trading partner behind the United States.”

But robust trade, investment and economic ties do not a world order make. The biggest impediment to a Chinese-led arrangement of alliances is acute global suspicion of China’s intentions. On March 12, the European Commission released a paper labelling China an “economic competitor” and “a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance”.

Ahead of Mr Xi’s much-heralded arrival in Italy, French president Emmanuel Macron declared the “period of European naivety [on China] is over”. His finance minister, Jean-Yves Le Drian, said China’s plan for a new Silk Road “must be one that goes in both directions”. And Germany’s foreign minister, Heiko Maas, suggested countries that believe “they can do clever business with the Chinese… will be surprised when they wake up and find themselves dependent”.

Add to that the doleful American pronouncements about deals with China. Ahead of Italy signing the agreement with Mr Xi, US president Donald Trump’s National Security Council tweeted that it merely “lends legitimacy to China’s predatory approach to investment and will bring no benefits to the Italian people”.

Clearly, three competing factors are at play here. Washington is piqued — and panicky — about ceding ground and influence to Beijing. Second, the US, EU and other countries have legitimate complaints against China over market access for foreign companies, forced technology transfers to Chinese firms, and intellectual property rights. But third, and perhaps most important, the momentum is currently with China.

While Mr Trump’s America seems to be in retreat, China constantly expresses enthusiasm about engaging with the world. Its willingness to spend on roads, railways, ports and power stations across Asia, Africa and Europe has elicited support from Azerbaijan to Zimbabwe. As Italy’s deputy prime minister Luigi Di Maio, who also serves as minister of economic development, said of the deal cut with Mr Xi: “Like someone in the United States said ‘America first’, I continue to repeat ‘Italy first’ in commercial relations.”

Cross-cultural links are being forged with great seriousness. Saudi Arabia plans to teach the Chinese language in schools. British universities are offering “fully funded scholarships” to Fudan University in Shanghai. And China’s influence on the world as we know it was made clear by the recent grounding of Boeing 737 Max planes. China became the first to take this step, and once the Europeans followed, the US had no choice but to reluctantly acquiesce.

It’s not yet a new dawn for the Xin World Order, but to reorientate the 19th-century English poet Arthur Hugh Clough’s famous words: eastward, look, the sky is bright.