Editing DNA will be as significant for us as vaccines to our granddads

“Engineering the perfect baby,” screams the headline in Technology Review. It’s their “featured story” and explores the rather alarming fact that “scientists are developing ways to edit the DNA of tomorrow’s children.”

“Engineering the perfect baby,” screams the headline in Technology Review. It’s their “featured story” and explores the rather alarming fact that “scientists are developing ways to edit the DNA of tomorrow’s children.”

There’s a reason that Antonio Regalado’s piece is pretty much in the realm of sci-fi. He starts by describing George Church’s lab on the Harvard Medical School campus. Here, he says, “you can find researchers giving E. Coli a novel genetic code never seen in nature. Around another bend, others are carrying out a plan to use DNA engineering to resurrect the woolly mammoth. His lab, Church likes to say, is the center of a new technological genesis—one in which man rebuilds creation to suit himself.”

And then he goes on to describe a conversation with Luhan Yang, a Harvard recruit from Beijing, who explains “germline editing”. This means altering the DNA of either the egg or the sperm – or perhaps even the embryo. Ms Yang says that the editing could be a means of eliminating disease genes or passing genetic fixes on to our children. Whole families might no longer be afflicted by cystic fibrosis. People could ensure they would be protected against Alzheimer’s. She adds that people might be able to genetically their progeny against the effects of aging.

To my layperson’s mind, these sound like epochal advances and as significant perhaps as antibiotics and vaccines.

But that’s if they’re allowed to happen.

There are whispers that a project is underway in China. One in the US, which Ms Yang mentions to the writer, is not really underway, she later says. And Britain, which controversially became the first country in the world to allow so-called “three-person babies”, had to go against the clergy’s objections. Many countries (but not the US) have banned germline engineering, several scientific bodies say it might be risky and the European Union’s convention on human rights and biomedicine says it is a human rights crime to tamper with the gene pool.

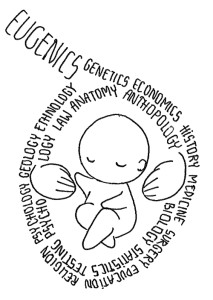

That sounds odd when, as previously discussed, eugenics is already socially accepted in many ways. We have learnt to live with hybrid crops, egg-freezing, sperm donor-selection and testing mature pregnant women to make sure the foetus doesn’t have Down syndrome. Why the reluctance to end disease where and when possible?