How India’s ambitious plan for digital government grew into a monster

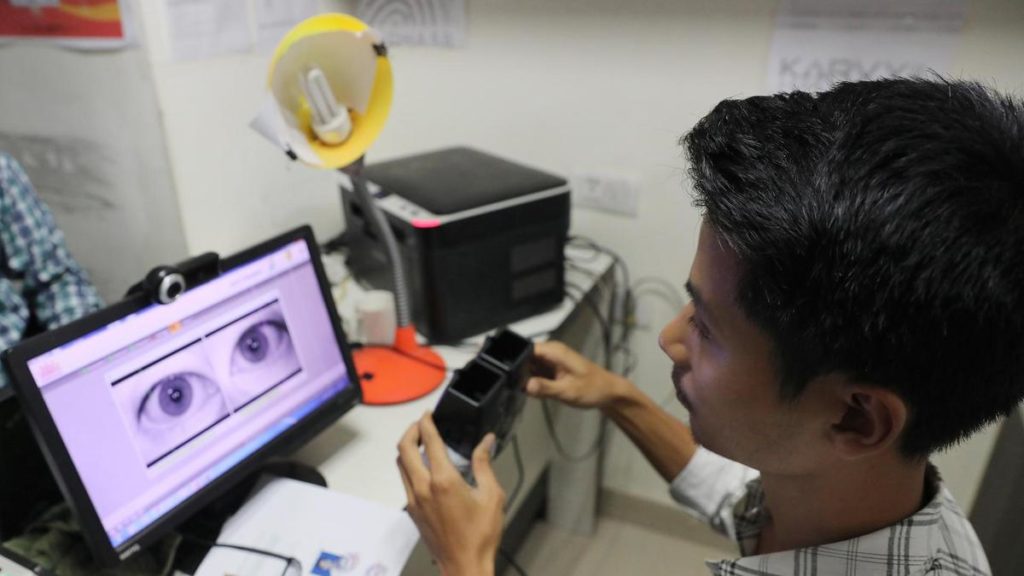

A retina scanner is used for a young boy’s unique identification card, or Aadhaar, in New Delhi. Rajat Gupta / EPA

The Aadhaar biometric data scheme has become synonymous with invasive government and attempted control

In the decade since India created a government agency to collect residents’ data for Aadhaar, the world’s largest biometric identification scheme, a lot has happened. Aadhaar has been a resounding success — in purely numerical terms at least — achieving nearly universal coverage in a vast country of 1.3 billion people. And at the same time, it has been a dreadful failure, underlining the limits of relying on data to digitally reboot the Indian system and transform people’s lives.

Worse, Aadhaar, a Hindi word that means “foundation”, might actually have been regressive. It has put many Indians off the whole idea of e-government and the notion that an ID card, a PIN number and a fingerprint scan can magically end the hassle of dealing with the state, rendering all transactions smooth and instantaneous.

In fact, Aadhaar has become a synonym for invasive government and attempted control in India today. The 12-digit Aadhaar number, which is tied to a person’s name, gender, address, date of birth, and the biometric information recorded from 10 fingerprints and both irises, is now being seen as an assault on privacy. It is also regarded as an insidious tool that might facilitate mass surveillance by the state for political or communal ends. In September, a lawyer for petitioners challenging Aadhaar’s reach and sweep told the Indian Supreme Court that it was an “electronic leash” to which every resident of India was tethered.

That was emotive language but it reflected the heightened passions around this issue. How did it all go so wrong? On the face of it, Aaadhar seemed like a simple plan to digitise basic information about people living in India, making it easier for them to access government services. It should have been liberating for a densely populated and often chaotically administered country such as India. In his 2015 book Rebooting India, Nandan Nilekani, the architect of Aadhaar, who founded India’s largest tech company Infosys, described the biometric ID scheme in poetic terms. It is a way, Mr Nilekani said, to “make every Indian, no matter how poor or marginalised, visible to the state”.

But just how visible, to whom, in what way, to what extent, and why, have become the difficult issues for Aadhaar. For the past few years it has been embroiled in controversy over the Indian authorities’ attempt to make the Aadhaar number mandatory for every transaction by a resident — from tax payments to bank accounts, mobile phone numbers and even the simplest of online purchases. Meanwhile access to food aid and healthcare for the poorest, most vulnerable Indians, has not been eased by Aadhaar. Nor have loan applications by farmers.

There have also been reported data leaks, theft, misuse and overuse. In January last year, an Indian journalist bought a bootlegged Aadhaar database with details of one billion Indians for 500 rupees (about $8). It called into question the rigour with which the Indian authorities secure Aadhaar data. Around the same time, Reetika Khera, a development economist at Delhi’s Indian Institute of Technology, publicised the results of a survey she conducted with other economists in Jharkhand, eastern India. Their comparison of villages that did and did not implement the Aadhaar system for buying grain yielded dispiriting conclusions. Those that complied with Aadhaar suffered more than those that ignored the scheme. Middle class India, meanwhile, grew concerned about the insistence of banks, mobile phone companies and other private service providers to link to their Aadhaar accounts.

Rather than a convenient tool, Aadhaar seemed to have metamorphosed into a monstrous, all-consuming entity that would swallow up individuals and spit them out as a number, as the lawyer arguing against the scheme in the Supreme Court said last year.

There are three points to make about Aadhaar. It is highly ambitious; it could still be a force for good; but it has been grossly mismanaged.

Data collection and streamlined national identity card systems can work well, as countries like Sweden have shown. For 72 years — the entire time India has been an independent country — Sweden’s mandatory national ID number has been linked to tax, school, medical and other citizen records. Swedes see that as a convenience rather than an imposition.

Estonia is a more recent example of using digitised data to make government work well for all who live in the small Baltic country. A digital signature is enough for official documents. An ID card and a PIN allow online voting, legal business agreements and much more besides. Now Estonia even has e-residency, which allows people overseas to incorporate businesses in the country.

Clearly, there is potential for India’s Aadhaar to become a digitised tool for genuine development. But as India contemplates another development tool — branded “artificial intelligence for all” — Aadhaar is a reminder that data collection can’t always address systemic problems.