Is ever closer European union unwittingly making populism more popular?

It’s not always possible to agree with Yanis Varoufakis, a former finance minister of Greece. In early 2015, Mr Varoufakis’s combative stance towards the European Union (and leather jacket) seemed to symbolise Athens’ defiant mood towards Europe-wide fiscal discipline.

Even so, there is some reason to pay attention to Mr Varoufakis’s words and opinions in his more recent avataar of Professor of Economics at the University of Athens. Mr Varoufakis’s commentary is especially interesting in the context of more recent developments in Italy. Not too long ago, he offered an excellent diagnosis of the rise of populism in Europe. It’s essentially a result of ever closer European union, he said.

How?

Apparently, a recent European Commission report on the economic imbalances afflicting each EU member state, blames the Italian government for its failure to rein in debt. The Commission, Mr Varoufakis wrote, lamented the effects of Italy’s actions and inaction. The Commission said, in Mr Varoufakis’s words, this “has spooked the bond markets, pushed interest rates up, and thus shrunk investment”. He went on to suggest that Italy’s xenophobic deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini was actually rather pleased with the report, which “presents a splendid opportunity to blame the Commission itself for Italy’s travails, by arguing that it was actually the EU’s fiscal austerity policies which constricted growth, pushed the economy to the brink of a new recession”. That report was, of course, issued before the Italian government entered a period of stasis with the prime minister’s resignation.

But both the European Commission and Mr Salvini were right – and both were also wrong, said Mr Varoufakis.

For, “Italy is, in an important sense, Europe’s Japan. Both economies are typified by a strong export-oriented industrial sector, a current-account surplus, similar terms of trade, terrible demographics, and, following years of imprudent lending, zombie-like banks. Moreover, they are also alike in the composition of their financial liabilities, featuring relatively low private debt and very high public debt.”

But Japan, unlike Italy, has not had Eurozone fiscal restrictions to deal with. Its central bank has printed money as needed, which allowed the country’s political centre to hold.

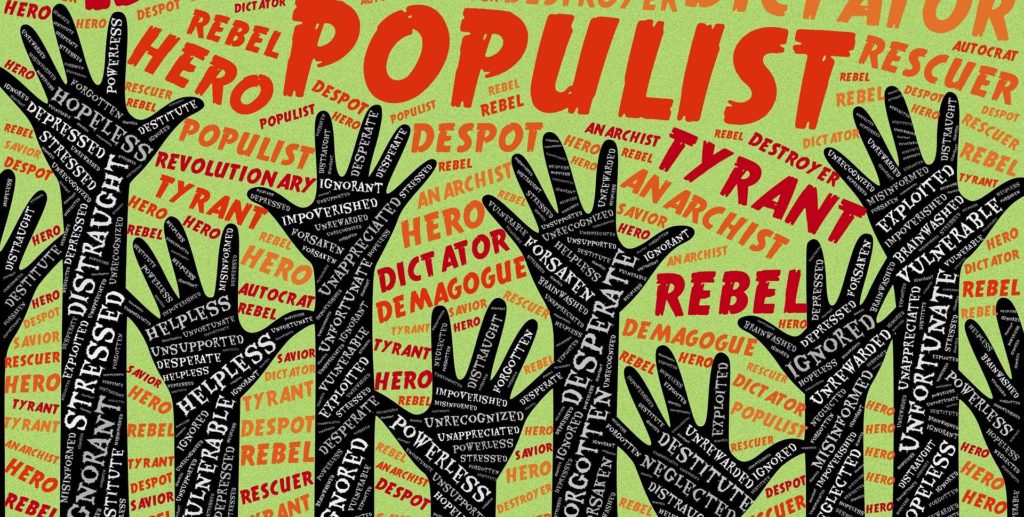

European union, ever closer union, has allowed politicians like Mr Salvini to rise.