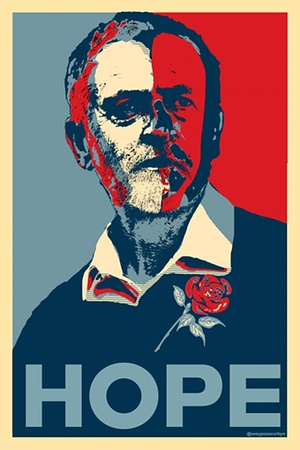

Jeremy Corbyn is the sort of Englishman who inspires something other than contempt

There was a time that Indians spoke of the British with awe. Indians were amazed that people from a small faraway island could have subdued so large and populous a country as theirs. That awe has faded now, as has the memory of colonial rule.

There was a time that Indians spoke of the British with awe. Indians were amazed that people from a small faraway island could have subdued so large and populous a country as theirs. That awe has faded now, as has the memory of colonial rule.

My grandfather, for instance, was jubilant that the British were forced to leave in 1947, ending the Raj. But having studied at the London School of Economics with the prominent economist Harold Laski, my grandfather had great respect for British intellectual inquiry, discipline and reasonableness. (Some might say that should read “apparent reasonableness”, but I don’t think my grandfather would have seen Laski in that way.) Anyway, years after my grandfather returned to India and became dean of the faculty of commerce at Lucknow University, his daughter, my mother, arrived in Britain to take specialized medical exams. She initially stayed with Frida Laski, by then a widow. It was a sign of the deep bond between the British professor and his Indian student that their families remained affectionately in touch.

Contact, of course, creates bonds of affection. This is as true for individuals as for countries.

Sometimes a more distant view can be harsher. It is not too extreme to say that India looked at its former imperial master from across the seas in a fairly critical way.

Post-imperial Britain was a country in shock – the loss of its core basis for political, financial and cultural dominance was gone with the end of the Raj. It took most of the remainder of the 20th century for Britain, a country in transition, to stabilize itself and to come to terms with its new, reduced role in the world. In the process, sometimes it sold itself short, assuming positions that did it no credit (Tony Blair’s decision to support George W. Bush’s Iraq invasion, for instance).

The “natives”, as Cecil Rhodes called the dark-skinned indigenous people of the colonies, watched, their lips faintly curled. The British, it seemed to them, were proving that they were morally bankrupt, along with having been exploitative hypocrites for hundreds of years. Didn’t they, many Indians thought, steal our wealth for centuries and then expect us to thank them for building a railway network to transport the purloined goods?

Along with having lost an empire, the British it seemed, were publicly willing to be seen to lose all moral fibre too. Leaders like Mr Blair, the oleaginous and values-free David Cameron and now, the right-wing-leaning Theresa May, only seemed to confirm the decline of any attempt at British moral authority.

(When she was home secretary, Theresa May epitomized the sort of hypocrisy the former “natives” were unlikely to view indulgently. The UK wanted better access to India’s banking and other sectors even as Mrs May remained unrelenting in her opposition to providing visas to Indian visitors, students and IT specialists. She wants our money, many Indians thought, but not our people. How insulting is that. )

Okay, so I’ve gone on long enough. What does any of this, you might ask, have to do with Jeremy Corbyn, the unfashionably socialist leader of the UK’s Labour Party.

Just this.

He may be exasperating for some; and not quite prime minister material for others. But he’s an old politician who remains idealistic still, a touching and uplifting reality in a formulaic world of political focus groups and canned messages. As Mr Corbyn said in his Friday speech at Chatham House, “I want to see a peaceful world”, a message that was as authentic as his obvious old-fashioned courtesy to questions from the audience and his apparent enthusiasm about the “UN representative of Somalia” who was also there.

I think my grandfather would probably have admired Mr Corbyn just like he did Laski. He would have thought that Jeremy Corbyn is the sort of Englishman who inspires something other than contempt.