Myanmar artist Sai reveals junta’s horrors

Sai’s latest exhibition is taking place in London

A new exhibition in London by artist Sai reveals the horrors of an overlooked conflict

A bold new exhibition by a young Myanmar artist challenges people not to turn away from dead babies and brutalised women in conflict zones overlooked by the world’s media.

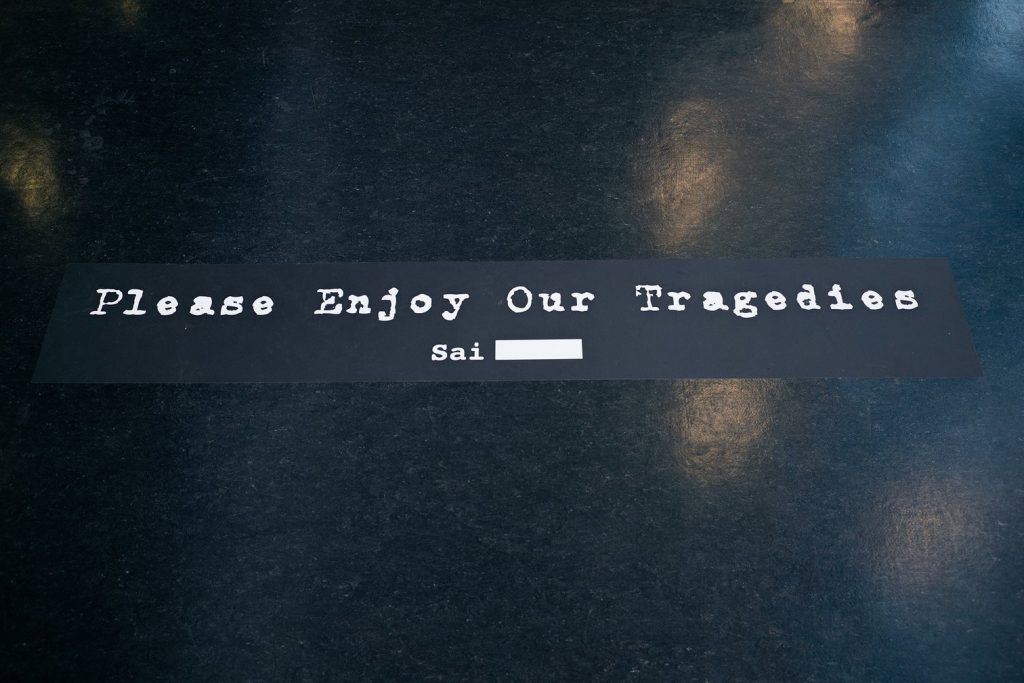

The London show, ‘Please Enjoy Our Tragedies’, is by Sai, a multimedia artist who blocks out his last name for security reasons. Some of Sai’s work will be shown at the Venice Biennale from 23 April, as part of the European Cultural Centre’s Personal Structures exhibition.

While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine currently dominates global attention, Sai draws links between that conflict and domestic repression in Myanmar. “The same stakeholders are involved in Myanmar as in Ukraine,” he told openDemocracy. “Russia arms Myanmar’s generals and China supports them. It’s not a Ukraine problem; it’s a global problem.”

The reference is to a report by the United Nations special rapporteur on Myanmar, Thomas Andrews, published one year after Myanmar’s military junta seized power on 1 February 2021. The report said the military had shown flagrant disregard for human life and deliberately targeted civilians using weapons provided by “UN Security Council members China and Russia”. Serbia and India also continue to sell weapons to Myanmar. Sai added that Ukraine had stopped arms sales to Myanmar after the coup.

On 21 March, the UN rapporteur summed up the human toll of the coup. The junta, said Andrews, had murdered more than 1,600 civilians, detained more than 10,000, displaced more than half a million and destroyed more than 4,500 homes, all while spreading armed conflict to regions previously at peace. International action on Ukraine, he added, is the standard by which the world’s response to the crisis in Myanmar should henceforth be measured.

Sai opened Facebook on his mobile phone, scrolling down rapidly. “See, we have the same problems as Ukraine. A little baby shot in the head, villages burnt down. Our newsfeeds are a very visual documentation of Myanmar’s suffering.”

The exhibition also works like a newsfeed in different mediums — fabric, images, videos — documenting the political turmoil that has engulfed Myanmar as well as the personal tragedies of its people.

That includes Sai’s own family. His father, Linn Htut, was chief minister of Shan state in the east of the country when the coup took place in 2021. Appointed to this post by the now-deposed leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy, Sai’s father had already been elected to the regional assembly in Myanmar’s landmark 2015 polls, which ended nearly 50 years of military rule.

“There was just one month left to go in his term,” Sai said. But his father was accused of corruption, thrown into prison and sentenced to 16 years hard labour. His wife, a former judge, was placed under house arrest, and Sai, their only child, went on the run along with daughter-in-law, ‘K’, a human rights activist.

Sai decided to use his art to show the world Myanmar’s painful reality. “Doing art is about using evidence,” he explained — to show the truth and serve as a fact-checker for the junta’s narrative.

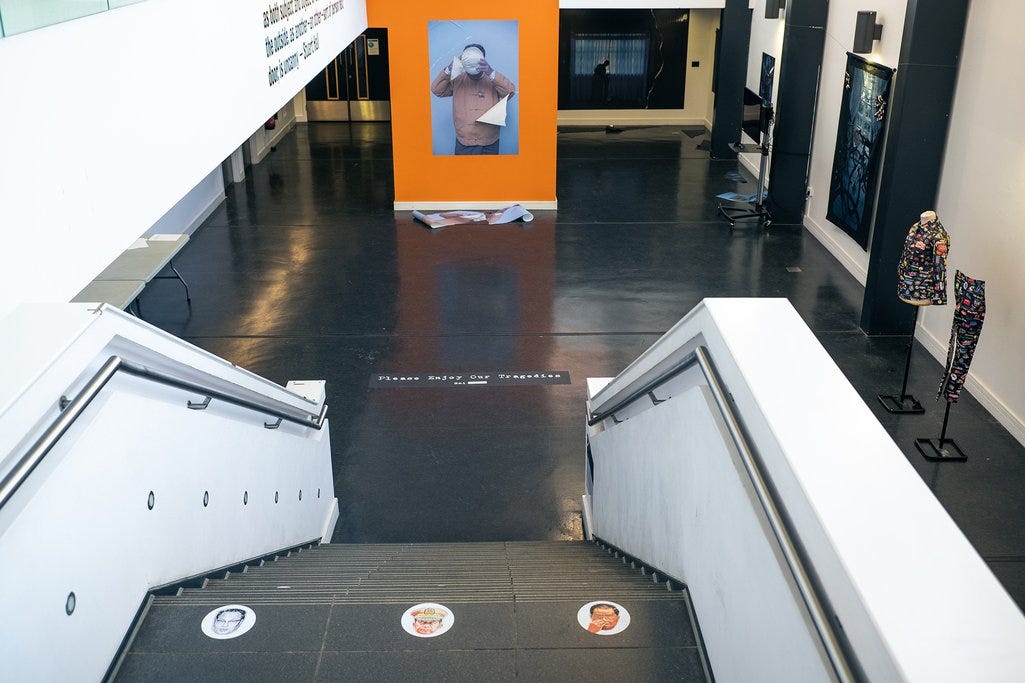

Stickers of Myanmar’s current and former military rulers — generals Min Aung Hlaing, Than Shwe and Ne Win — march across the steps leading down to the exhibition. Three short films set the tone, showing a child’s pain at the plight of an incarcerated and tortured parent, a common enough story across Myanmar today. Sai and K made the films during a covert visit to the chief minister’s official residence, where Sai put on his father’s clothes, as if to hold him close. The camera watches as Sai stands in the corner of a dark room, scratching at the wall, a desperate, ineffectual act born out of his inability to push away the solid reality of political oppression.

A two- by one-metre fabric image bears two rosettes, each with 150 petals, at either corner. The petals are woven from the clothes of prisoners killed by the junta since the coup. Sai explains that he wove in the style of a Shan carpet because, “Myanmar’s problems are always swept under the carpet, but when we become the carpet itself, no one can sweep us under it.”

A headless mannequin wears a suit of clothes in a piece titled ‘Military Trouser’. Complete with shoulder epaulettes, it’s a parody of a Myanmar military uniform, the tough raincoat-like fabric adorned with brand logos such as Myanmar Brewery, Padonmar Soap, Army Rum, and Black Shield Stout. These are just some of the hundreds of businesses within the Myanmar military’s enormous empire. It has run for 60 years and has stakes in everything from booze to banking, tobacco to tourism.

Sai said he made the suit of clothes as a warning to the Myanmar people: “Don’t give money to fund the bullet that’s going to kill us.” According to a 2019 UN report, business revenues have enabled the military to carry out human rights abuses with impunity. Through a network of businesses and affiliates, the UN said the Tatmadaw, as the Myanmar military is called, has been able to “insulate itself from accountability and oversight”.

Indeed, in the year since the 2021 coup, Myanmar’s generals have plunged the country into crisis. The fledgling democratic transition of the past decade has been reversed. The kyat, Myanmar’s currency, has lost 60% of its value, driving up the cost of imports. Foreign investors such as French giant TotalEnergies, US oil major Chevron, and Australia’s Woodside Petroleum have left.

And in December, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) said a new survey of Myanmar respondents confirmed projections that nearly half of the country’s 55 million population will be below the national poverty line in 2022. The UNDP said Myanmar’s poverty headcount will return “to levels not seen since 2005, effectively erasing 15 years of pre-pandemic economic growth”.

It’s a cruel blow to a country hailed just a few years ago by management consultancy McKinsey as an “outperformer” with GDP growth of at least 5% from 1995 to 2016. In 2015, the World Bank reclassified Myanmar from low-income to lower-middle income.

But now Myanmar is on the downward slide and the world seems not to care, lamented Sai — neither about its pain nor its ongoing revolution. People are fighting for their tomorrow, as part of the People’s Defence Force, an armed militia. Myanmar’s protestors say that the collective resistance is a sign that their country, too, is a brave nation, one that the world should deem worth fighting for. Some of Sai’s sponsors say that his creative works are a reminder of the many affronts to democracy and human rights across the world and that small acts of resistance by artists like Sai are more important than ever.

Soon after the coup, Sai designed a clear polycarbonate shield to protect protestors from rubber bullets and then handed the instructions over for free dissemination throughout Myanmar via social media. He believes artists have a duty to briefly put down their paintbrushes for the cause and build whatever is needed.

But the exhibition — “art rooted in tragedy” — also has its own logic, he added. “If you spit gum on the road, no one will care. If everyone spits gum on the road at the same point, it becomes a big mound, an unavoidable problem. I’m hoping my art will be the first of many pieces of gum.”

Originally published at https://www.opendemocracy.net.