Taos Pueblo’s new church still throbs with old colonial traumas

The 1850 adobe building carries within it an element of eloquently expressed pain

In Taos Pueblo, the Unesco World Heritage site that preserves a 1,000-year way of life some 90 minutes from Santa Fe, the new church underlines the lingering ambivalences and resentments from the Spanish colonial period.

The old church, San Geronimo de Taos, lies in ruins as I previously mentioned. (Click here for my blog on the Red Willow Creek people’s continuing sense of trauma over the 176-year-old massacre.)

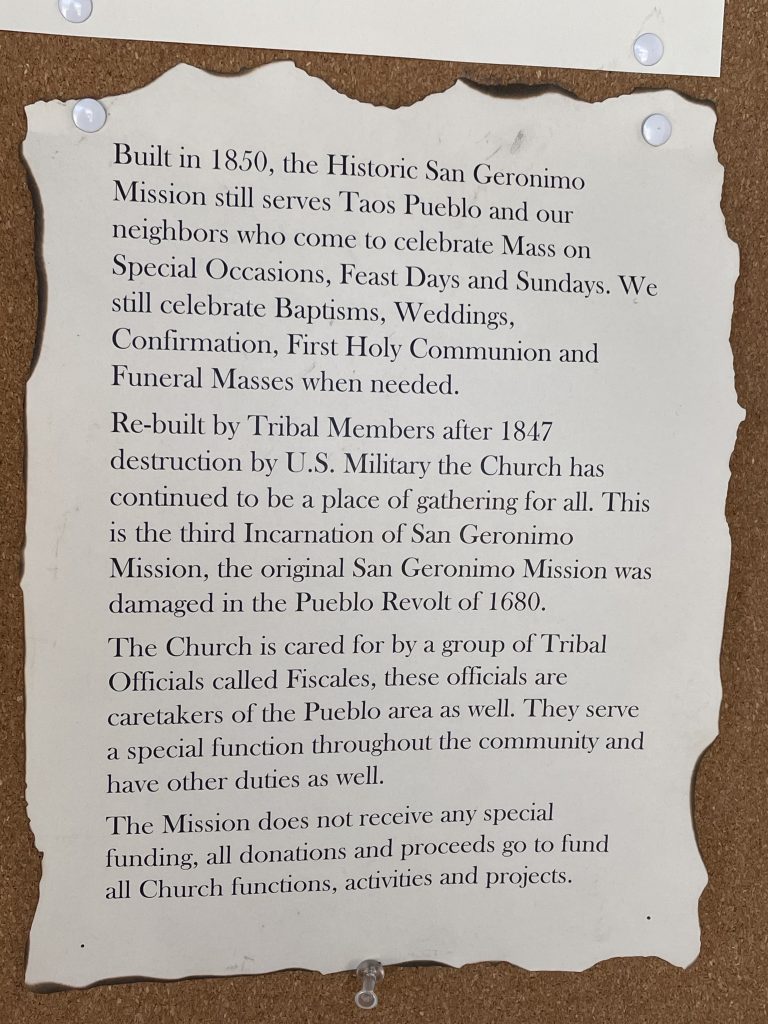

The new church, which isn’t really very new having been built in 1850, also carries within it an element of pain. Eloquently expressed pain. A pain that is deliberately embraced.

This rather striking example of northern New Mexican architecture is clearly a church that is of the Red Willow Creek people. It has statues of the Virgin Mary and Jesus and also reveals the Pueblo’s determination to continue traditional practices.

It’s striking that to the right of the altar, lies a coffin. Ariane, the Taos Pueblo woman who interpreted what we saw for us, said the coffin commemorates the body of Jesus and is in remembrance of her people’s “forced conversions” (to Catholicism).

What might that mean? It’s an unusual feature in a Catholic church. According to the basic tenets of Catholicism, that Jesus was crucified, died, buried within a tomb, resurrected three days later and his body ascended to heaven.

But don’t the majority (90 per cent or thereabouts) of the Red Willow Creek people identify as Catholics?

Yes, but with a deep sense of resentment, a mutinous nod to what happened and a yearning for what might have been.

Taos symbolises the way the 17th century Spanish conquest of this part of the world played out, as well as its after effects. The old church was one of the earliest Spanish religious missions, religious and economic institutions created by the European colonisers to convert and instruct native peoples in their religion and culture. They were part of the larger Spanish colonial strategy and aroused intense feelings among the communities they were built to supposedly serve.

According to the US National Park Service, Taos Pueblo received its first Catholic Franciscan priest in 1598. That was the year Juan de Onate, the explorer who led early Spanish expeditions to the Great Plains and lower Colorado River Valley, established the first capital of provincial Spanish territory.

The Spanish settlement, Santa Fe de Nuevo México, had its capital in San Gabriel de Yungue-Ouinge, not far from the Taos Pueblo. De Onate assigned Fray Francisco de Zamora as missionary to the Taos area. Some 30 years later (1627), one of his successors reported that a church was under construction but that the Indians were not particularly cooperative. A couple decades later, the Pueblo people were complaining to the Inquisition in Mexico that the priest was an immoral sort and he and several other Spaniards were killed and the church destroyed. Around 1660, they reluctantly accepted another Catholic priest and the church was slowly rebuilt even as the Red Willow Creek people chafed under the restrictions and retributions imposed by the Spanish colonisers for any sign of traditional religious practice.

In 1680, the native American leader Popay took up residence in Taos, from where he launched a coordinated uprising against the Spanish throughout northern New Mexico. The Pueblo Revolt, as it came to be called, drove the Spanish out of the region, albeit for a mere 12 years. Taos took three more years to submit to the 1692 Reconquista led by Don Diego de Vargas and even then its rebellious streak flashed through. It rebelled in 1696, before finally yielding.

The Taos mission, being in a ruined state, was reportedly destroyed. But the Franciscans, leery of the Pueblo’s bolshie-ness, did not despatch any priests to the Pueblo until 1706. When they did, Fray Juan Álvarez reportedly began rebuilding the adobe church, which was finished in 1726 and stood for less than a century.

The Spanish bell in the ruined San Geronimo Church

In 1846, the church was riddled with cannon balls and left in ruins, while 150 women and children were massacred as they sheltered within.

As it turns out, the new church that took the place of the old seems hardly more emollient as a symbol. That coffin next to the altar says everything.

“Our battered suitcases were piled on the sidewalk again; we had longer ways to go. But no matter, the road is life”

– Jack Kerouac

Also read: