Trump’s moral equivalence between Nazis & anti-Nazis? Read this 30-year-old essay

Donald Trump sees a moral equivalence between neo-Nazis and those who protest againt them. Thirty-one years ago, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations, explained the myth of moral equivalence. It’s worth reading, click here to do so. Or carry on below for the high points.

Donald Trump sees a moral equivalence between neo-Nazis and those who protest againt them. Thirty-one years ago, Jeane Kirkpatrick, Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations, explained the myth of moral equivalence. It’s worth reading, click here to do so. Or carry on below for the high points.

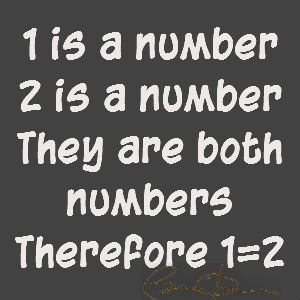

But a key point to note is the essay’s relevance today. It rejects moral relativism.

And it disdains “both sides-ism” to coin a phrase, something American conservatives have always condemned. Back in 2011, remember, Paul Ryan, current speaker of the US House of Representatives, told the conservative Weekly Standard: “If you ask me what the biggest problem in America is, I’m not going to tell you debt, deficits, statistics, economics — I’ll tell you it’s moral relativism.”

On then to Ms Kirkpatrick’s essay. At the time she wrote it, the US and the Soviet Union were alleged to have moral equivalence. Both were nuclear-armed superpowers. Both, as she wrote, “contend for dominance and resemble one another in key respects.” This has projected an “image of moral and political symmetry”, says Ms Kirpatrick, one that “has gained a wide acceptance not only in the Third World, but also among our allies and ourselves.”

This happened, said Ms Kirkpatrick because a moral equivalence was portrayed using the following modus operandi:

- “To destroy a society it is first necessary to delegitimize its basic institutions so as to detach the identifications and affections of its citizens from the institutions and authorities of the society marked for destruction. This delegitimization may be achieved by attacking a society’s practices in terms of its own deeply held values, or it may be achieved by attacking the values themselves. The latter course was undertaken by the fascists and Nazi movements which rejected outright the basic values of Western liberal democratic civilization. They rejected democracy, liberty, equality, and forthrightly, frankly, embraced principles of leadership, obedience and hierarchy as alternatives to the hated basic values of democracy.”

- “…it is suggested that we do not respect our own values, it is claimed by the Soviets that they do. Our flaws are exaggerated, theirs are simply denied…(So) not a dime’s worth of difference between these two regimes.”

This produced the following result, Ms Kirkpatrick noted:

“It’s perfectly clear that the tendency to self-debasement, self-denigration which has been so brilliantly commented upon by the French scholar Jean-Francois Revel and others recently is rooted in this practice of measuring Western democratic societies by utopian standards. There is simply no way that such measurements can result in anything but chronic, continuous self-debasement, self-criticism, and finally, self-disgust.”

The essay notes the attempts to systematically redefine “terms of political discourse… making it very difficult to think thoughts other than those indicated by the definition.”

In human rights, for instance, “violations are failures of governments, vis-a-vis their citizens. Terrorist groups do not violate human rights in the current vernacular; only governments violate human rights.”

The essay concludes with a quote from Richard Weaver’s book, Ethics of Rhetoric. He wrote, “We must recognize and defend a concept of meaning to which that concept of value is, of course, absolutely essential: a concept of epistemological stability, if you will, a concept of reality which is not, in fact, a function of power and does not shift from day to day to fit the political needs of a totalitarian group.

That remains true today, just as much when the US and Soviet Union were battling to assume the moral high ground.