TV wars between India and Pakistan are only half the story

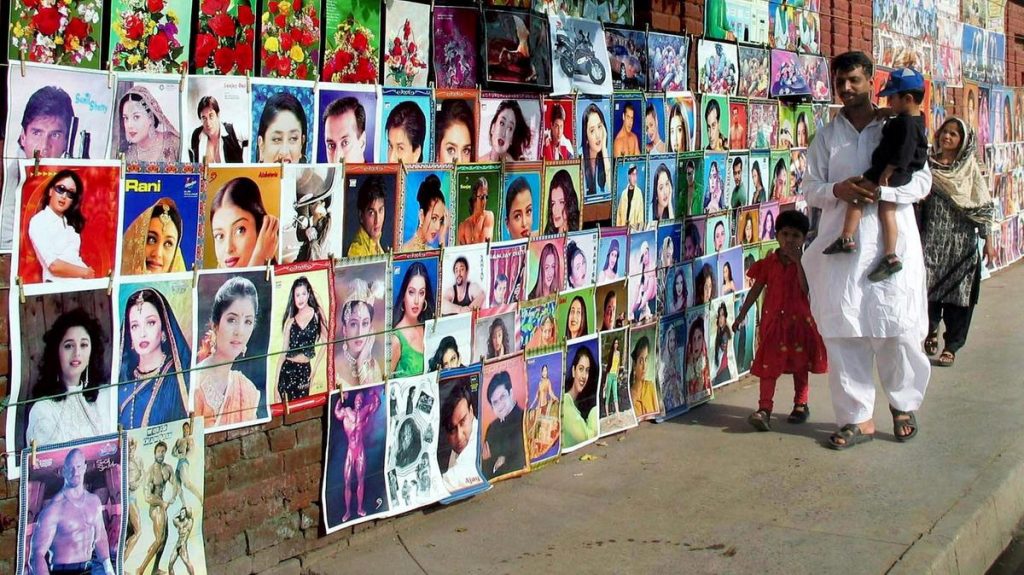

Indian film posters on display in Pakistan. EPA

Television is a medium, American comedian Fred Allen once quipped, because anything well done is rare. That’s a damning value judgement — but worth thinking about now that Pakistan’s Supreme Court has reinstated a ban on Indian television shows in retaliation for its neighbour’s alleged attempt to dam the Indus river and its tributaries.

What’s the point of turning off the flow of Indian television shows to Pakistan? Is it purely symbolic, a sign of worse to come or just another example of the two countries’ sporadic, often petty displays of hostility towards each other?

This type of antagonism has history. In September 2016, the Indian Motion Pictures Producers Association imposed a ban on Pakistani artists working in the Bollywood industry, citing the strained diplomatic relations between the two countries. Indian minister Babul Supriyo went so far as to criticise the hiring of world-renowned Pakistani singers such as Atif Aslam and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, saying producers should show national “solidarity”.

The new Pakistani ban is a reprisal of a broader one from 2016, which was lifted last year. The fallout says a lot more than a diplomatic demarche. It sends a message, one that is deadly serious, of the grimness with which Pakistan views any perceived attempt by India to reduce the flow of water. The rivers flow through Indian-administered Kashmir and more than 80 per cent of Pakistan’s agricultural land relies on them for irrigation.

Although India denies accusations of “stealing” Pakistan’s water, the consequences of any such attempt would be significant for its neighbour’s water supply. But so too is Pakistan’s blocking of Indian soap operas, police dramas, quiz shows and Bollywood films. They have a large and passionate following in Pakistan and are a subtle but significant way for India to exert what historian Edward Carr once called “power over opinion”.

That is why it mattered when China cut off South Korea’s wildly popular cultural exports in 2016. It had already made known its vehement opposition to the deployment of the US Terminal High Altitude Area Defence missile system in South Korea. But Beijing’s refusal until recently to allow Korean dramas, K-pop concerts and fan meets delivered the message more effectively. It hit the South Koreans where it really hurt — a lucrative relationship with Chinese financiers and massive exposure in a billion-dollar market. More to the point, it made K-pop’s biggest stars personae non gratae in China, even those who made efforts to release songs in Mandarin.

By not acknowledging the Korean entertainment industry, the Chinese seemed to damn an entire people with indifference. Those engaged in the sector urgently sought new audiences and tried to localise their acts to suit sensibilities in Japan, the US and the Middle East, including the UAE. But it was hard going, bad for their sense of self-worth and a huge blow to low-cost cultural messaging from Seoul.

Americans know this well. The relationship between US films and foreign policy is minutely documented. During the Second World War, the US held 16mm film screenings in European villages. The use of American films picked up during the Cold War as a riposte to the Soviet threat and to build favourable mindsets abroad through realistic yet alluring images of US society. After 9/11, senior Bush administration official Karl Rove tried to enlist Hollywood in the so-called war on terror.

Somewhat similar attempts to harness filmmaking to foreign policy objectives have been employed by Russia and Georgia in the years since they clashed in a short but brutal war in 2008. In an obvious attempt to press their respective cases on the big screen, Russian filmmakers released a documentary and romantic feature film that depicted Georgia as a genocidal aggressor, after which the Georgian government supported a Hollywood director’s take on the conflict.

But if image projection — nation-branding in today’s parlance — needs flattering films, persuasive TV shows and alluring creative content, it can also be unmade by it. This has long been the case for Japan and its one-dimensional portrayal in hundreds of Chinese films, year on year. After his recent visit to Beijing, Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe, once labelled an “unwelcome person” by Chinese officials, said bilateral ties were at a “historic turning point”. Just how historic might really only be seen on the big screen.

Earlier this year, China and Japan signed a landmark co-production treaty bringing their film industries — second and third respectively behind the US in domestic box office revenue — closer together. Potentially the agreement will end the powerful and insistent cinematic rendering by China of decades of entrenched bitterness and rivalry with Japan. It had a profoundly negative effect on Japan’s image, as Tokyo University professor and former defence ministry researcher Yasuhiro Matsuda once acknowledged. There are facts, he said, such as the Nanjing massacre and Japan’s invasion of China, but “when there are more than 200 movies coming out (in one year), you can imagine the negative effect”.

Well, quite. Muhammad Iqbal, the poet known as the spiritual father of Pakistan, once wrote: “Nations are born in the hearts of poets, they prosper and die in the hands of politicians”. In the age of multimedia, those poets and storytellers are now television producers, film directors and social media users.