Libya stories from a British businessman who knew everyone & was related to everyone else

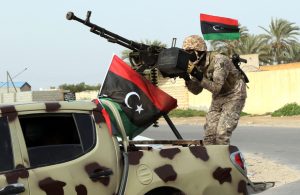

A member of a brigade loyal to the Fajr Libya (Libya Dawn), an alliance of Islamist-backed fighters, in Sabratha, west of the capital Tripoli, in February 2016. The state of chaos has changed since then

The French president’s mediated deal between rival Libyan leaders brought to mind the British Libyan businessman I met just the other day. He seemed to know everyone worth knowing in the country of his birth and was related to everyone else.

As we sat at Tunis Carthage Airport and waited for the laggardly Tunisian national carrier Tunis Air to prepare for departure two hours late, Mr Libya (as I will call him) was greeted by a trim man in a blue shirt. “That’s the head of security for Fayez Al Sarraj,” Mr Libya said, referencing the UN-backed prime minister of Libya as he waved back at the blue-shirt. “He was a colonel in the airforce,” he went on. He meant the Libyan airforce from before the fall of Muammar Gaddafi for the country has had no national army from 2011.

It was hard not to be impressed by Mr Libya’s fund of stories. One of his relatives, it turned out, had helped arrange Mr Al Sarraj’s extraordinary sneak-sail in April 2016 from Tunisia to the Tripoli naval base where his government is headquartered. One of Mr Libya’s brothers (or an uncle, I forget which) is a security heavyweight in Tripoli. Another did something else equally important.

Mr Libya was admiring of Mr Al Sarraj’s efforts to govern a state of chaos. His administration, remember, is one of three in ungoverned Libya. There is the General National Council in Tripoli, the one in Tobruk in the east and then there is Mr Al Sarraj’s outfit.

So what’s in prospect for the country, I asked my fellow passenger. “When I go to Tripoli,” he replied, “my family says I should carry a gun if I want to drive myself. I refuse – I’ve never handled a gun – and I tell them I’d rather not drive at all. But in the last three weeks it’s been getting better.”

Why, I asked. What’s changed?

“The Qatar crisis has meant the troublemakers aren’t getting paid anymore,” he said, meaning the militias. Mr Al Sarraj’s government, said my fellow passenger, had also seized the moment by limiting the money dispensed by banks.

I don’t doubt the effectiveness of starving a market of cash but wondered if the Qatar crisis could really have had so significant an effect on Libya. We were speaking some seven weeks after the Gulf Quartet’s spat with Qatar began. Even if Mr Libya’s allegation were accurate, money flows rarely run so dry so fast. If so, most countries could deal with insurgencies, militants and others rather more expeditiously than usually happens.