How safe is our world, really?

Here’s the full version of the Feb14 This Week, Those Books. Sign up for free at https://thisweekthosebooks and get the post the day it drops

Welcome to This Week, Those Books, your rundown on books new and old that resonate with the week’s big news story.

The few minutes it takes to read this newsletter will make you smarter, faster. Or click on the audio button above for a human, not AI, voiceover by my close collaborator Michael. These book suggestions come with a summary and quotes. So even if you don’t read the actual book, you’ll be able to discuss it. I never recommend a book I don’t like and I look through a number every week to find the few I share. Find me on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook or YouTube.

Another book giveaway at over 7,200 subscribers!

We’re celebrating YOU, fabulous reader, as we hit a milestone: More than 7,200 subscribers in nearly 100 countries. Grab your chance to win Takeaway by Angela Hui, which featured in the last post. To enter the competition, answer by February 22: what animal are you in the Chinese horoscope?

Yours,

The Big Story:

The 60th Munich Security Conference, described as the world’s biggest security gathering, gets underway with some 50 heads of state or government and key international leaders. Meanwhile, hot wars rage and political unpredictability rises across the globe.

Normally seen as a transatlantic gab-fest, this year’s Conference emphasises the Global South.

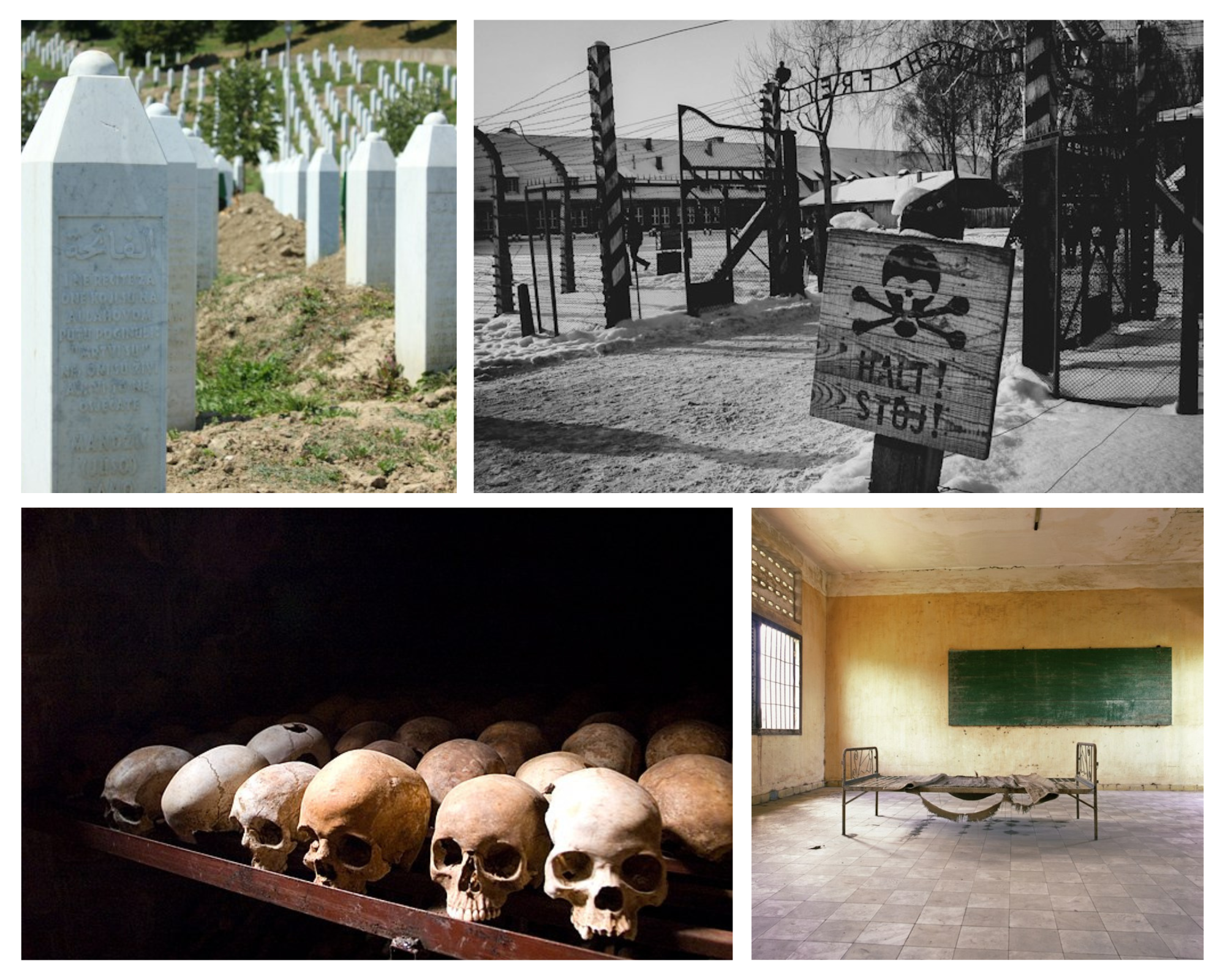

But is the world becoming more or less safe? Less, says the Global Peace Index, which ranked 163 countries or 99.7% of the world’s population and found that average global peacefulness is decreasing.

“Around the globe, more people are dying in fighting, being forced from their homes or in need of life-saving aid than in decades,” the non-profit International Crisis Group declared on New Year’s Day 2024.

It’s true, the world map is blotchy with blood and tears:

- Israel’s punishing military operations in Gaza have gone on four months, killing at least 28,000 Palestinians and leaving more than 50% of Gaza’s buildings damaged or destroyed.

- As Ukraine prepares for the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, civilian casualties are at 10,000, according to the United Nations. The military death toll is estimated at 25,000 Ukrainian and 120,000 Russian soldiers. American military aid, Ukraine’s main support, has become uncertain because of US domestic politics and Russia’s Vladimir Putin justifies the invasion saying its roots go back to the ninth century.

- Sudan’s devastating 10-month war has killed at least 12,000, displaced more than seven million, “reignited ethnic tensions…(and) could inflame neighbouring countries”, according to the Vatican.

- In Myanmar, three years after the military deposed the elected government, pro-democracy protestors and armed ethnic groups are fighting the junta, which has just announced compulsory military service. Neighbouring Bangladesh, China and India are watching closely.

Three other ways the world feels less safe:

- America is increasingly seen as a less reliable lynchpin in a shifting global order.

- Cheap killer drones are changing warfare…in Ukraine, in Myanmar and on crucial global trade pathways as Yemen’s Houthis attack ships in the Red Sea.

- “Migration through war and climate change” is seen as one of the world’s most pressing security threats, according to the February 12 Munich Security Report, which surveyed 12,000 people in the G7 countries, as well as Brazil, India, China and South Africa.

The Backstory:

- The Munich Security Conference was founded in 1963 by Ewald von Kleist, a German army officer who participated in a military plot to assassinate Hitler.

- Regional variants are increasingly in fashion:

– The first Central Asian Forum on Security and Cooperation took place last July.

– In April, Ethiopia will hold the Tana Forum, billed as “Africa’s equivalent of the Munich Security Conference”.

– The IISS Shangri-La Dialogue will discuss Asia’s security challenges in Singapore in May, as it has done since 2002.

This Week, Those Books:

- A well-known scholar of war discusses human security.

- Suspenseful stories show the 21st century is no time to die for British spies.

- Global Security Cultures

By: Mary Kaldor

Publisher: Polity

Year: 2018

London School of Economics professor Mary Kaldor starts by addressing the “general sense of foreboding” that marks our times, the vague sense that the world is about to face some terrible tragedy.

But the tragedy is already happening, she says. Refugees are drowning, innocent people are being starved, prohibited chemical weapons are back in action and vehicles have been turned into weapons. It’s “not a war in the 20th century sense. It is something else”.

Hence this book. To make sense of the “something else”.

Kaldor suggests that 21st century world politics is marked by four different “security cultures” – geopolitics, new wars, liberal peace, and the War on Terror. She asks an important question: “Whose safety are we talking about – that of the individual, the nation, the state, the world?” And on what terms, considering security is a very ambiguous concept. It means safety or freedom from care but also refers to an apparatus or set of practices such as locks, airport scanners, police, military and so on.

Kaldor wonders why politicians see war as the answer to security problems such as terrorism despite the long list of dreadful examples where it didn’t work – Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Mali etc.

- The Slough House series (Books 1 to 8)

By: Mick Herron

Publisher: Soho / John Murray

Year: Starting 2010

These eight books update the worldwide cult of the British secret agent to reflect the spies of today and the new threats they face – Islamist and right-wing extremism, Putin’s resurgent Russia, corrupt fat cats, populist politicians. In 1953, when Ian Fleming published his first James Bond novel, 007 was as dashing as Britain fancied herself to be. The country had not felt the full effects of de-colonisation, the loss of power and influence and the drying up of cash pipelines from its vast overseas empire. Mick Herron updates the whole frame of the spy novel. Slough House is a derelict office for failed spies, routinely dubbed “slow horses”; its boss Jackson Lamb is sloppy, overweight and prone to passing gas, and Britain is in a hideously self-destructive post-Brexit mode – poorly maintained and polarised, its public servants as venal, vengeful and self-serving as anywhere.

The Slough House books have turned into a hit Apple TV+ series (fellow Substackers have written on this here and here), which means more people have probably watched Lamb and his slow horses than read about them.

But the books ARE worth reading…if only for the acerbic wit.