Make no mistake, the ‘servant’ problem still exists

As I read The Spectator’s spiffing review of Lucy Lethbridge’s new book, ‘Servants: A Downstairs View of Twentieth-century Britain’, I was reminded of the house we went to see on spec here in Port au Prince. The US Embassy rents it and they rather wondered if we wanted to move into that property, rather than the smaller, eggbox we are assigned.

The house-on-spec was simply enormous – on four levels with umpteen flights of stairs in between floors and in between different levels on the same floor. It seemed to have lots of useless unusable space, no assigned dining room, a dark, small and windowless kitchen, with a larger kitchen directly across the courtyard from it.

We wandered around the compact set of rooms adjoining the larger kitchen. Clearly, they were meant for the ‘help’. But the large kitchen was surprising. Surely the staff wouldn’t have a larger kitchen than the big house?

But of course they would. This is Haiti. The main house wouldn’t do the real cooking and all the food would be brought across the courtyard and carried up and down the multiple flights of stairs by the ‘help’.

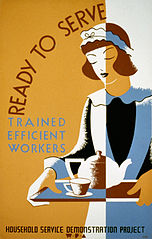

So it exists. ‘Servanthood’, for all that it’s now a politically incorrect term , still exists as a word, a state of being and often as a dreadful inequity – in countries like Haiti, India and in the Gulf states.

Everywhere else – the US, UK, Europe – there are rights, many protections and a supremely egalitarian inclusiveness for the armies of au pairs, nannies, cleaners and gardeners employed by double-income, time-poor families.

Thank God for that. As Lethbridge details, the British system regarded servants as human machines. It cared little about the effect of, say, a cooler north-facing kitchen (with very little light) on the individuals who spent 15 hours a day there. All that mattered was the food kept cool for longer in the days before refrigeration. She recounts Mrs Panton’s advice on servants’ bedrooms in ‘Hints for Young Housekeepers’: These should be “merely places where they lie down to sleep as heavily as they can” because prettiness and comfort are wasted on them.

After WWII, the British servant system started to be dismantled but even today, according to the International Labour Organization, there are at least 50 million domestic workers (or possibly twice that number because this sort of work often stays unregistered) in 117 countries.

Lethbridge herself says there were as many domestics in London in 2011 as in the 19th century and the au pair-cleaner figure is very much a 21st century fixture (albeit, one who is well-compensated and often treated as a friend). They wouldn’t be assigned that compact set of rooms (with the large kitchen) I just went to see in Port au Prince.