Malala week: Every foreign plaudit makes her more suspect in Pakistan

Malala Week for us, whoops ABC on twitter. The BBC doesn’t say as much but it too is using the anniversary of the Taliban’s attack on Malala Yousafzai as a news peg. On Monday night (October 7), the BBC’s Panorama programme featured the 16-year-old confidently (and rather self-importantly, some might say) describing herself as a campaigner for education, a children’s rights activist and a women’s rights activist. On Monday night too, ABC broadcast Diane Sawyer’s interview with Malala.

Malala Week for us, whoops ABC on twitter. The BBC doesn’t say as much but it too is using the anniversary of the Taliban’s attack on Malala Yousafzai as a news peg. On Monday night (October 7), the BBC’s Panorama programme featured the 16-year-old confidently (and rather self-importantly, some might say) describing herself as a campaigner for education, a children’s rights activist and a women’s rights activist. On Monday night too, ABC broadcast Diane Sawyer’s interview with Malala.

Everyone is hedging their bets. On Friday, the Nobel Peace Prize is to be announced. Might Malala win? Even if she doesn’t, she’ll be hobnobbing with the great and the good Friday week, October 18. Malala has been invited to a reception hosted by the Queen at Buckingham Palace.

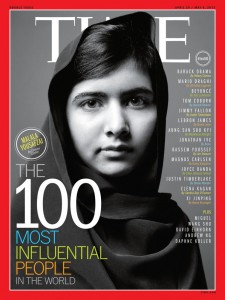

It is the latest in a series of honours heaped on a young woman who nearly died at the hands of bigots for the crime of wanting to study. Malala made a landmark speech at the United Nations, has been honoured at Harvard University and in her current home, Birmingham.

But with every foreign prize, every news story, every preferment, Malala becomes ever more alien and suspect to Pakistan. This can only grow after ‘Malala week’.

On the BBC, she defended the West as more than “short dresses and skirts”. She said such garments do “not mean they (the West) have a different ideology.” It is a plea for tolerance that is likely to be misrepresented and profoundly misunderstood.

On the Panorama programme, Anglo-Pakistani presenter Mishal Hussain returned to the valleys she herself had once known as a child on holiday. In Swat, she found Malala’s former classmates proud of her, but almost everywhere else, particularly in Islamabad, there was suspicion of her prominence in the West. Even Sartaj Aziz, urbane and so much a man of the world, was doubtful about Malala’s relevance to the debate about education in Pakistan. Mr Aziz, the Pakistani prime minister’s adviser on national security and foreign affairs, refused to describe her as a national embarrassment but insisted she conveyed an inaccurate picture of girls’ education in his country. “The image it created…is not true,” he said.

It’s hardly new, this tendency to shoot the famous messenger, especially one who brings bad news. The parallel is not exact by any means, but remember Aravind Adiga’s Booker Prize-winning novel ‘The White Tiger’, in which he brilliantly captured the unspoken voice of people from “the Darkness”, the impoverished areas of rural India? India Shining didn’t like it.